Friday, December 23, 2016

Tuesday, December 20, 2016

Sunday, December 18, 2016

Friday, December 16, 2016

Thursday, December 15, 2016

Monday, August 1, 2016

In

all about Portrait Photography,

b&w,

Portrait Photography

by Unknown

//

11:00 AM

//

Leave a Comment

Portrait Photography

All About Portrait Photography

The relatively low cost of the daguerreotype in the middle of the 19th century and the reduced sitting time for the subject, though still much longer than now, led to a general rise in the popularity of portrait photography over painted portraiture. The style of these early works reflected the technical challenges associated with long exposure times and the painterly aesthetic of the time. Subjects were generally seated against plain backgrounds and lit with the soft light of an overhead window and whatever else could be reflected with mirrors. Advances in photographic equipment and techniques developed, and gave photographers the ability to capture images with shorter exposure times and the making of portraits outside the studio.

Winter portrait of a 10-month-old baby girl

When portrait photographs are composed and captured in a studio, the photographer has control over the lighting of the composition of the subject and can adjust direction and intensity of light. There are many ways to light a subject's face, but there are several common lighting plans which are easy enough to describe.

One of the most basic lighting plans is called three-point lighting. This plan uses three (and sometimes four) lights to fully model (bring out details and the three-dimensionality of) the subject's features.

Also called a main light, the key light is usually placed to one side of the subject's face, between 30 and 60 degrees off center and a bit higher than eye level. The purpose of the Key-Light is to give shape (modelling) to a subject, typically a face. This relies on the first principle of lighting, white comes out of a plane and black goes back into a plane. The depth of shadow created by the Main-Light can be controlled with a Fill-Light.

In modern photography, the fill-in light is used to control the contrast in the scene and is nearly always placed above the lens axis and is a large light source (think of the sky behind your head when taking a photograph). As the amount of light is less than the key-light (main-light), the fill acts by lifting the shadows only (particularly relevant in digital photography where the noise lives in the shadows). It is true to say that light bounces around a room and fills in the shadows but this does not mean that a fill-light should be placed opposite a key-light (main-light) and it does not soften shadows, it lifts them. The relative intensity (ratio) of the Key-light to the fill-light is most easily discussed in terms of "Stops" difference (where a Stop is a doubling or halving of the intensity of light). A 2 Stop reduction in intensity for the Fill-Light would be a typical start point to maintain dimensionality (modelling) in a portrait (head and shoulder) shot.

Accent-lights serve the purpose of accentuating a subject. Typically an Accent-light will separate a subject from a background. Examples would be a light shining onto a subject's hair to add a rim effect or shining onto a background to lift the tones of a background. There can be many accent lights in a shot, another example would be a spotlight on a handbag in a fashion shot. When used for separation, i.e. a hair-light, the light should not be more dominant than the main light for general use. Think in terms of a "Kiss of moonlight", rather than a "Strike of lightning", although there are no "shoulds" in photography and it is up to the photographer to decide on the authorship of their shot.

A Kicker is a form of Accent-Light. Often used to give a backlit edge to a subject on the shadow side of the subject.

Director Josef von Sternberg used butterfly lighting to enhance Marlene Dietrich's features in this iconic shot, from Shanghai Express, Paramount 1932 - photograph by Don English

Butterfly lighting uses only two lights. The key light is placed directly in front of the subject, often above the camera or slightly to one side, and a bit higher than is common for a three-point lighting plan. The second light is a rim light.

Butterfly lighting uses only two lights. The key light is placed directly in front of the subject, often above the camera or slightly to one side, and a bit higher than is common for a three-point lighting plan. The second light is a rim light.

Often a reflector is placed below the subject's face to provide fill light and soften shadows.

This lighting may be recognized by the strong light falling on the forehead, the bridge of the nose, the upper cheeks, and by the distinct shadow below the nose that often looks rather like a butterfly and thus, provides the name for this lighting technique.

Butterfly lighting was a favourite of famedHollywood portraitist George Hurrell, which is why this style of lighting often is called,Paramount lighting, as well.

These lights can be added to basic lighting plans to provide additional highlights or add background definition.

Not so much a part of the portrait lighting plan, but rather designed to provide illumination for the background behind the subject, background lights can pick out details in the background, provide a halo effect by illuminating a portion of a backdrop behind the subject's head, or turn the background pure white by filling it with light.

Most lights used in modern photography are aflash of some sort. The lighting for portraiture is typically diffused by bouncing it from the inside of an umbrella, or by using a soft box. A soft box is a fabric box, encasing a photostrobe head, one side of which is made of translucent fabric. This provides a softer lighting for portrait work and is often considered more appealing than the harsh light often cast by open strobes. Hair and background lights are usually not diffused. It is more important to control light spillage to other areas of the subject. Snoots, barn doorsand flags or gobos help focus the lights exactly where the photographer wants them. Background lights are sometimes used with color gels placed in front of the light to create coloured backgrounds.

Window light used to create soft light to the portrait

Windows as a source of light for portraits have been used for decades before artificial sources of light were discovered. According to Arthur Hammond, amateur and professional photographers need only two things to light a portrait: a window and a reflector. Although window light limits options in portrait photography compared to artificial lights it gives ample room for experimentation for amateur photographers. A white reflector placed to reflect light into the darker side of the subject's face, will even the contrast. Shutter speeds may be slower than normal, requiring the use of a tripod, but the lighting will be beautifully soft and rich.

While using window light, the positioning of the camera can be changed to give the desired effects. Such as positioning the camera behind the subject can produce asilhouette of the individual while being adjacent to the subject give a combination of shadows and soft light. And facing the subject from the same point of light source will produce high key effects with least shadows.

There are essentially four approaches that can be taken in photographic portraiture — the constructionist, environmental, candid, and creative approach. Each has been used over time for different reasons be they technical, artistic or cultural. The constructionist approach is when the photographer in their portraiture constructs an idea around the portrait — happy family, romantic couple, trustworthy executive. It is the approach used in most studio and social photography. It is also used extensively in advertising and marketing when an idea has to be put across. The environmental approach depicts the subject in their environment be that a work, leisure, social or family one. They are often shown as doing something, a teacher in a classroom, an artist in a studio, a child in a playground. With the environmental approach more is revealed about the subject. Environmental pictures can have good historical and social significance as primary sources of information. The candid approach is where people are photographed without their knowledge going about their daily business. Whilst this approach taken by the paparazzi is criticized and frowned upon for obvious reasons, less invasive and exploitative candid photography has given the world superb and important images of people in various situations and places over the last century. The images of Parisians by Doisneauand Cartier-Bresson demonstrate this approach. As with environmental photography, candid photography is important as a historical source of information about people. The Creative Approach is where digital manipulation (and formerly darkroom manipulation) is brought to bear to produce wonderful pictures of people. It is becoming a major form of portraiture as these techniques become more widely understood and used.

Lenses used in portrait photography are classically fast, medium telephoto lenses, though any lens may be used, depending on artistic purposes. See Canon EF Portrait Lenses for Canon lenses in this style; other manufacturers feature similar ranges. The first dedicated portrait lens was the Petzval lens developed in 1840 by Joseph Petzval. It had a relatively narrow field of view of 30 degrees, a focal length of 150mm, and a fastf-number in the f/3.3-3.7 range.

Portrait taken with an 18mm wide-angle lens with an aperture of ƒ/4.5, resulting in fairly large depth of field

Classic focal length is in the range 80–135mm on 135 film format and about 150-400mm on large format, which historically is first in photography. Such a field of viewprovides a flattening perspective distortionwhen the subject is framed to include their head and shoulders. Wider angle lenses (shorter focal length) require that the portrait be taken from closer (for an equivalent field size), and the resulting perspective distortion yields a relatively larger nose and smaller ears, which is considered unflattering andimp-like. Wide-angle lenses – or even fisheye lenses – may be used for artistic effect, especially to produce a grotesque image. Conversely, longer focal lengths yield greater flattening because they are used from further away. This makes communication difficult and reduces rapport. They may be used, however, particularly in fashion photography, but longer lengths require a loudspeaker or walkie-talkie to communicate with the model or assistants. In this range, the difference in perspective distortion between 85mm and 135mm is rather subtle; see (Castleman 2007) for examples and analysis.

Speed-wise, fast lenses (wide aperture) are preferred, as these allow shallow depth of field (blurring the background), which helps isolate the subject from the background and focus attention on them. This is particularly useful in the field, where one does not have a back drop behind the subject, and the background may be distracting. The details ofbokeh in the resulting blur are accordingly also a consideration; some lenses, in particular the "DC" (Defocus Control) types by Nikon, are designed to give the photographer control over this aspect, by providing an additional ring acting only on the quality of the bokeh, without influencing the foreground (hence, these are not soft-focus lenses). However, extremely wide apertures are less frequently used, because they have a very shallow depth of field and thus the subject's face will not be completely in focus. Thus, f/1.8 or f/2 is usually the maximum aperture used; f/1.2 or f/1.4 may be used, but the resulting defocus may be considered a special effect – the eyes will be sharp, but the ears and nose will be soft.

Speed-wise, fast lenses (wide aperture) are preferred, as these allow shallow depth of field (blurring the background), which helps isolate the subject from the background and focus attention on them. This is particularly useful in the field, where one does not have a back drop behind the subject, and the background may be distracting. The details ofbokeh in the resulting blur are accordingly also a consideration; some lenses, in particular the "DC" (Defocus Control) types by Nikon, are designed to give the photographer control over this aspect, by providing an additional ring acting only on the quality of the bokeh, without influencing the foreground (hence, these are not soft-focus lenses). However, extremely wide apertures are less frequently used, because they have a very shallow depth of field and thus the subject's face will not be completely in focus. Thus, f/1.8 or f/2 is usually the maximum aperture used; f/1.2 or f/1.4 may be used, but the resulting defocus may be considered a special effect – the eyes will be sharp, but the ears and nose will be soft.

Conversely, in environmental portraits, where the subject is shown in their environment, rather than isolated from it, background blur is less desirable and may be undesirable, and wider angle lenses may be used to show more context.

Finally, soft focus (spherical aberration) is sometimes a desired effect, particularly inglamour photography where the "gauzy" look may be considered flattering. The Canon EF 135mm f/2.8 with Softfocus is an example of a lens designed with a controllable amount of soft focus.

Most often a prime lens will be used, both because the zoom is not necessary for posed shots (and primes are lighter, cheaper, faster, and higher quality), and because zoom lenses can introduce highly unflattering geometric distortion (barrel distortion or pincushion distortion). However, zoom lenses may be used, particularly in candid shots or to encourage creative framing.

Portrait lenses are often relatively inexpensive, because they can be built simply, and are close to the normal range. The cheapest portrait lenses are normal lenses(50mm), used on a cropped sensor. For example, the Canon EF 50mm f/1.8 II is the least expensive Canon lens, but when used on a 1.6× cropped sensor yields an 80mm equivalent focal length, which is at the wide end of portrait lenses.

Source:Wikipeida

Monday, July 4, 2016

In

equipment,

everything you need to know about street photography,

street photography,

the all about series

by Unknown

//

11:45 AM

//

1 comment

Street Photography

Street photography is photography conducted for art or enquiry that features unmediated chance encounters and random incidents within public places. Street photography does not necessitate the presence of a street or even the urban environment. Though people usually feature directly, street photography might be absent of people and can be of an object or environment where the image projects a decidedly human character in facsimile or aesthetic.

"The photographer is an armed version of the solitary walker reconnoitering, stalking, cruising the urban inferno, the voyeuristic stroller who discovers the city as a landscape of voluptuous extremes. Adept of the joys of watching, connoisseur of empathy, the flâneur finds the world "picturesque.""

The street photographer can be seen as an extension of the flaneur, an observer of the streets (who was often a writer or artist).

Framing and timing can be key aspects of the craft with the aim of some street photography being to create images at a decisive or poignant moment.

Street photography can focus on people and their behavior in public, thereby also recording people's history. This motivation entails having also to navigate or negotiate changing expectations and laws of privacy, security and property. In this respect the street photographer is similar to social documentary photographers or photojournalists who also work in public places, but with the aim of capturing newsworthy events; any of these photographers' images may capture people and property visible within or from public places. The existence of services like Google Street View, recording public space at a massive scale, and the burgeoning trend of self-photography (selfies), further complicate ethical issues reflected in attitudes to street photography.

Much of what is regarded, stylistically and subjectively, as definitive street photography was made in the era spanning the end of the 19th century through to the late 1970s; a period which saw the emergence of portable cameras that enabled candid photography in public places.

Most kinds of portable camera are used for street photography; for example rangefinders, digital and film SLRs, and point-and-shoot cameras.

An example of a hand-held portable camera, the Leica I

The commonly used 35 mm full-frame format-focal lengths of 28 mm to 50 mm, are used particularly for their angle of view and increased depth of field, with wide-angle lenses potentially permitting a candid close approach to the human subjects without their suspecting they are in the frame. However there are no exclusions as to what might be used.

With zone focusing, the photographer chooses to set the focus to a specific distance, knowing that a certain area in front of and beyond that point will be in focus. The photographer only has to remember to keep their subject between those set distances.

The hyperfocal distance technique makes as much as possible acceptably sharp so that the photographer is freed up even further, from not having to consider the subject's distance, other than not being too close. The photographer sets the focus to a fixed point particular to the lens focal length, and the chosen aperture, and in the case of digital cameras their crop factor. Thus everything from a specific distance (that will typically be close to the camera), all the way to infinity, will be acceptably sharp. The wider the focal length of the lens (i.e. 28 mm), and the smaller the aperture it is set to (i.e. f/11), and with digital cameras the smaller their crop factor, the closer to the camera is the point at which starts to become acceptably sharp.

Alternatively waist-level finders and the articulating screens of some digital cameras allow for composing, or adjusting focus, without bringing the camera up to the eye and drawing unwanted attention to the photographer.

Anticipation plays a role where a relevant or ironic background that might act as a foil to a foreground incident or passer-by is carefully framed beforehand; it was a strategy much used for early street photographs, most famously in Cartier-Bresson's figure leaping across a puddle in front of a dance poster in Place de l'Europe, Gare Saint Lazare, 1932.

Tony Ray-Jones listed the following shooting advice to himself in his personal journal:

Be more aggressive Get more involved (talk to people)Stay with the subject matter (be patient)Take simpler pictures See if everything in background relates to subject matter Vary compositions and angles more Be more aware of composition Don’t take boring pictures Get in closer (use 50mm lens [or possibly ‘less,’ the writing is unclear])Watch camera shake (shoot 250 sec or above)Don’t shoot too much Not all eye level No middle distance

Street photography and documentary photography can be very similar genres of photography that often overlap while having distinct individual qualities.

Documentary photographers typically have a defined, premeditated message and an intention to record particular events in history. The gamut of the documentary approach encompasses aspects of journalism, art, education, sociology and history. In social investigation, often documentary images are intended to provoke, or to highlight the need for, societal change. Conversely, street photography is disinterested by nature, allowing it to deliver a relatively neutral depiction of the world that mirrors society, "unmanipulated" and with usually unaware subjects.

Tuesday, May 10, 2016

In

panorama,

panoramic photography,

the all about series,

wide angle lens

by Unknown

//

8:58 AM

//

Leave a Comment

Ways To Improve Your Panoramas

All About Panoramic Photography

Panoramic photography is a technique of photography, using specialized equipment or software, that captures images with horizontally elongated fields of view. It is sometimes known as wide format photography. The term has also been applied to a photograph that is cropped to a relatively wide aspect ratio, like the familiar letterbox format in wide-screen video.

While there is no formal division between "wide-angle" and "panoramic" photography, "wide-angle" normally refers to a type of lens, but using this lens type does not necessarily make an image a panorama. An image made with an ultra wide-angle fisheye lens covering the normal film frame of 1:1.33 is not automatically considered to be a panorama. An image showing a field of view approximating, or greater than, that of the human eye – about 160° by 75° – may be termed panoramic. This generally means it has an aspect ratio of 2:1 or larger, the image being at least twice as wide as it is high. The resulting images take the form of a wide strip. Some panoramic images have aspect ratios of 4:1 and sometimes 10:1, covering fields of view of up to 360 degrees. Both the aspect ratio and coverage of field are important factors in defining a true panoramic image.

Photo-finishers and manufacturers of Advanced Photo System (APS) cameras use the word "panoramic" to define any print format with a wide aspect ratio, not necessarily photos that encompass a large field of view. In fact, a typical APS camera in its panoramic mode, where its zoom lens is at its shortest focal length of around 24 mm, has a field of view of only 65°, which many photographers would only classify as wide-angle, not panoramic.

The device of the panorama existed in painting, particularly in murals as early as 20 A.D. in those found in Pompeii, as a means of generating an immersive 'panoptic' experience of a vista, long before the advent of photography. In the century prior to the advent of photography, and from 1787, with the work of Robert Barker, it reached a pinnacle of development in which whole buildings were constructed to house 360° panoramas, and even incorporated lighting effects and moving elements. Indeed, the careers of one of the inventors of photography, Daguerre, began in the production of popular panoramas and dioramas.

The development of panoramic cameras was a logical extension of the nineteenth-century fad for the panorama. One of the first recorded patents for a panoramic camera was submitted by Joseph Punch berger in Austria in 1843 for a hand-cranked, 150° field of view, 8-inch focal length camera that exposed a relatively large Daguerreotype, up to 24 inches (610 mm) long. A more successful and technically superior panoramic camera was assembled the next year by Friedrich von Martens in Germany in 1844. His camera, the Megaskop, used curved plates and added the crucial feature of setgears which offered a relatively steady panning speed. As a result, the camera properly exposed the photographic plate, avoiding unsteady speeds that can create an unevenness in exposure, called banding. Martens was employed by Lerebours, a photographer/publisher. It is also possible that Martens camera was perfected before Puchberger patented his camera. Because of the high cost of materials and the technical difficulty of properly exposing the plates, Daguerreotype panoramas, especially those pieced together from several plates (see below) are rare.

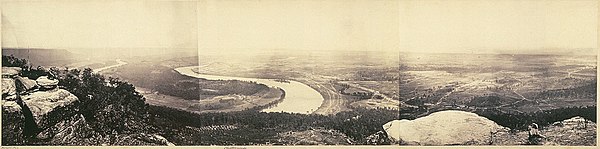

After the advent of wet-plate collodion process, photographers would take anywhere from two to a dozen of the ensuing albumen prints and piece them together to form a panoramic image (see: Segmented). This photographic process was technically easier and far less expensive than Daguerreotypes. Some of the most famous early panoramas were assembled this way by George N. Barnard, a photographer for the Union Army in the American Civil War in the 1860s. His work provided vast overviews of fortifications and terrain, much valued by engineers, generals, and artists alike.

Following the invention of flexible film in 1888, panoramic photography was revolutionised. Dozens of cameras were marketed, many with brand names indicative of their era; such as the Cylindrograph survey camera (1884), Wonder Panoramic(1890), Pantascopic (1862) and Cyclo-Pan (1970).

View from the top of Lookout Mountain, Tennessee, Albumen prints, February, 1864, by George N. Barnard

Short rotation, rotating lens and swing lens cameras have a lens that rotates around the camera's rear nodal point and use a curved film plane. As the photograph is taken, the lens pivots around its nodal point while a slit exposes a vertical strip of film that is aligned with the axis of the lens. The exposure usually takes a fraction of a second. Typically, these cameras capture a field of view between 110° to 140° and an aspect ratio of 2:1 to 4:1. The images produced occupy between 1.5 and 3 times as much space on the negative as the standard 24 mm x 36 mm 35 mm frame.

Cameras of this type include the Widelux,Noblex, and the Horizon. These have a negative size of approximately 24x58 mm. The Russian "Spaceview FT-2", originally an artillery spotting camera, produced wider negatives, 12 exposures on a 36-exposure 35 mm film.

Short rotation cameras usually offer few shutter speeds and have poor focusing ability. Most models have a fixed focus lens, set to the hyperfocal distance of the maximum aperture of the lens, often at around 10 meters (30 ft). Photographers wishing to photograph closer subjects must use a small aperture to bring the foreground into focus, limiting the camera's use in low-light situations.

Rotating lens cameras produce distortion of straight lines. This looks unusual because the image, which was captured from a sweeping, curved perspective, is being viewed flat. To view the image correctly, the viewer would have to produce a sufficiently large print and curve it identically to the curve of the film plane. This distortion can be reduced by using a swing-lens camera with a standard focal length lens. The FT-2 has a 50 mm while most other 35 mm swing lens cameras use a wide-angle lens, often 28 mm].

Rotating panoramic cameras, also called slit scan or scanning cameras are capable of 360° or greater degree of rotation. A clockwork or motorized mechanism rotates the camera continuously and pulls the film through the camera, so the motion of the film matches that of the image movement across the image plane. Exposure is made through a narrow slit. The central part of the image field produces a very sharp picture that is consistent across the frame.

Digital rotating line cameras image a 360° panorama line by line. Digital cameras in this style are the Panoscan and Eyes can. Analogue cameras include the Cirkut (1905),Leme (1962), Hulcherama (1979), Globuscope(1981) and Roundshot (1988).

Fixed lens cameras, also called flat back, wide view or wide field, have fixed lenses and a flat image plane. These are the most common form of panoramic camera and range from inexpensive APS cameras to sophisticated 6x17 cm and 6x24 cm medium format cameras. Panoramic cameras using sheet film are available in formats up to 10x24 inches. APS or 35 mm cameras produce cropped images in a panoramic aspect ratio using a small area of film. Advanced 35 mm or medium format fixed-lens panoramic cameras use the full height of the film and produce images with a greater image width than normal.

Pinhole cameras of a variety of constructions can be used to make panoramic images. A popular design is the 'oatmeal box', a vertical cylindrical container in which the pinhole is made in one side and the film or photographic paper is wrapped around the inside wall opposite, and extending almost right to the edge of, the pinhole. This generates an egg-shaped image with more than 180° view.

Because they expose the film in a single exposure, fixed lens cameras can be used with electronic flash, which would not work consistently with rotational panoramic cameras.

With a flat image plane, 90° is the widest field of view that can be captured in focus and without significant wide-angle distortion or vignetting. Lenses with an imaging angle approaching 120 degrees require a center filter to correct vignetting at the edges of the image. Lenses that capture angles of up to 180°, commonly known as fisheye lensesexhibit extreme geometrical distortion but typically display less brightness falloff thanrectilinear lenses.

With digital photography, the most common method for producing panoramas is to take a series of pictures and stitch them together. There are two main types: the cylindrical panorama used primarily in stills photography and the spherical panorama used for virtual-reality images.

Segmented panoramas, also called stitched panoramas, are made by joining multiple photographs with slightly overlapping fields of view to create a panoramic image. Stitching software is used to combine multiple images. In order to correctly stitch images together without parallax error, the camera must be rotated about the center of its entrance pupil. Some digital cameras can do the stitching internally, either as a standard feature or by installing a smartphone app.

Lens and mirror based (catadioptric) cameras consist of lenses and curved mirrors that reflect a 360 degree field of view into the lens' optics. The mirror shape and lens used are specifically chosen and arranged so that the camera maintains a single viewpoint. The single viewpoint means the complete panorama is effectively imaged or viewed from a single point in space. One can simply warp the acquired image into a cylindrical or spherical panorama. Even perspective views of smaller fields of view can be accurately computed.

The biggest advantage of catadioptric systems (panoramic mirror lenses) is that because one uses mirrors to bend the light rays instead of lenses (like fish eye), the image has almost no chromatic aberrations or distortions. The image, a reflection of the surface on the mirror, is in the form of a doughnut to which software is applied in order to create a flat panoramic picture, such software is normally supplied by the company who produces the system. Because the complete panorama is imaged at once, dynamic scenes can be captured without problems. Panoramic video can be captured and has found applications in robotics and journalism. The Mirror lens system uses only a partial section of the digital camera's sensor and therefore some pixels are not used. Recommendations are always to use a camera with a high Pixel count in order to maximize the resolution of the final image.

There are even inexpensive add-on catadioptric lenses for smartphones, such as the GoPano micro and Kogeto Dot.

Some cameras offer 3D features that can be applied when taking panoramic photographs. The technology enables the camera to take shots from different angles and combine them, creating a multidimensional effect. Some cameras use two different lenses to achieve the 3D effect, while others use one. Cameras such as Samsung NX1000, and Sony Cyber-shot DSC-RX1 offer the 3D Panorama mode.

A panoramic photograph of the Camp Nou stadium,Barcelona in January 2011

Source: Wikipedia

What Is Night Photography

All About Night Photography

The skyline of Singapore as viewed at night

In the early 1900s, a few notable photographers, Alfred Stieglitz and William Fraser, began working at night. The first known female night photographer is Jessie Tarbox Beals.The first photographers known to have produced large bodies of work at night were Brassai and Bill Brandt. In 1932, Brassai published Paris de Nuit, a book of black-and-white photographs of the streets of Paris at night. During World War II, British photographer Brandt took advantage of the black-out conditions to photograph the streets of London by moonlight.

Photography at night found several new practitioners in the 1970s, beginning with the black and white photographs that Richard Misrach made of desert flora (1975–77). Joel Meyerowitz made luminous large format color studies of Cape Cod at nightfall which were published in his influential book, Cape Light (1979). .Jan Staller’s twilight color photographs (1977–84) of abandoned and derelict parts of New York City captured uncanny visions of the urban landscape lit by the glare of sodium vapor street lights.

By the 1990s, British-born photographer Michael Kenna had established himself as the most commercially successful night photographer. His black-and-white landscapes were most often set between dusk and dawn in locations that included San Francisco, Japan, France, and England. Some of his most memorable projects depict the Ford Motor Company's Rouge River plant, the Ratcliffe-on-Soar Power Station in the East Midlands in England, and many of the Naziconcentration camps scattered across Germany, France, Belgium, Poland and Austria.

During the beginning of the 21st century, the popularity of digital cameras made it much easier for beginning photographers to understand the complexities of photographing at night. Today, there are hundreds of websites dedicated to night photography.

The length of a night exposure causes the lights on moving cars to streak across the image

The following techniques and equipment are generally used in night photography.

A tripod is usually necessary due to the long exposure times. Alternatively, the camera may be placed on a steady, flat object e.g. a table or chair, low wall, window sill, etc.A shutter release cable or self timer is almost always used to prevent camera shake when the shutter is released.Manual focus, since autofocus systems usually operate poorly in low light conditions. Newer digital cameras incorporate a Live View mode which often allows very accurate manual focusing.A stopwatch or remote timer, to time very long exposures where the camera's bulb setting is used.A camera lens with a wide aperture, preferably one with aspherical elements that can minimize coma

The long exposure multiple flash technique is a method of night or low light photography which use a mobile flash unit to expose various parts of a building or interior using along exposure.

This technique is often combined with using coloured gels in front of the flash unit to provide different colours in order to illuminate the subject in different ways. It is also common to flash the unit several times during the exposure while swapping the colours of the gels around to mix colours on the final photo. This requires some skill and a lot of imagination since it is not possible to see how the effects will turn out until the exposure is complete. By using this technique, the photographer can illuminate specific parts of the subject in different colours creating shadows in ways which would not normally be possible.

When the correct equipment is used such as a tripod and shutter release cable, the photographer can use long exposures to photograph images of light. For example, when photographing a subject try switching the exposure to manual and selecting the bulb setting on the camera. Once this is achieved trip the shutter and photograph your subject moving a flashlight or any small light in various patterns. Experiment with this outcome to produce artistic results. Multiple attempts are usually needed to produce a desired result.

Advanced imaging sensors along with sophisticated software processing makes low-light photography with High ISO possible without tripod or long exposure. Digital SLRs have high end APS-C sensors which have a very large dynamic range and high sensitivity making them capable of night photography.BSI-CMOS is another type of CMOS sensor that is gradually entering the compact camera segment which is superior to the traditional CCD sensors. Cameras with small sensors such as: Sony Cyber-shot DSC-RX100, Nikon 1 J2 and Canon PowerShot G1X give good images up to ISO 400.

Source: Wikipedia

Monday, May 9, 2016

In

all about medical photography,

doctors,

medical photography,

medicine,

Stereophotography,

surgery,

the all about series,

x rays

by Unknown

//

9:01 PM

//

Leave a Comment

Medical Photography

All About Medical Photography

G.-B. Duchanne de Boulogne, Synoptic plate 4 from Le Mécanisme de la Physionomie Humaine. 1862, albumen print. In the upper row and the lower two rows, patients with different expressions on either side of their faces

Medical Photography is a specialized area of photography that concerns itself with the documentation of the clinical presentation of patients, medical and surgical procedures, medical devices and specimens from autopsy. The practice requires a high level of technical skill to present the photograph free from misleading information that may cause misinterpretation. The photographs are used in clinical documentation, research, publication in scientific journals and teaching.

Medical photographers document patients at various stages of an illness, injuries and before and after surgical procedures. They record the work of healthcare professionals to assist in the planning of treatment and education of the public and other healthcare professionals. The nature of the work requires a respect for and sensitivity to people, an awareness of sterile procedures and an adherence to privacy legislation and policies.

The BioCommunications Association Inc., in a survey commissioned in 2008 of individuals working in medical photography, found that most medical photographers are employed by university affiliated hospitals and research centers. Ten percent were freelancers working in specialty clinics such as dermatology, ophthalmology and plastic surgery. A few of these provided services to the medical-legal profession. Medical photographers photograph patients in clinics, wards and in operating rooms. They may also be called to photograph an autopsy and gross specimens in the pathology department. Specialized photography techniques using photomacrography and ultra-violet and fluorescence photography may also be used. The role of the medical photographer has changed over the years from being exclusively medical to incorporating more general photography of a commercial or editorial nature to support public relations and education. Video production is playing an increased role; medical photographers are often responsible for video conferencing from operating rooms and are involved in tele-medicine. Departments employing medical photographers tend to number five people or less. Some medical photographers specialize in areas such as ophthalmology and dermatology.

Most medical photographers have a degree in photography from a college or university and frequently have a degree in the sciences. They need to have a good understanding of photographic and optical principles, and also understand the technical requirements of a particular job in order select or modify equipment. Knowledge of digital imaging software is necessary to edit and output images while maintaining scale and color balance.

An interest in science and medicine are important. A basic knowledge of anatomy and physiology coupled with a working knowledge of medical terminology is required in order to discuss the photographic needs with medical staff and other healthcare providers. Because they are working with patients, medical photographers must have the manners and sensitivity to make patients comfortable while being photographed. They must also be aware of the laws governing privacy and copyright.

The sciences were quick to realize the merits of photography because of its perceived ability to present an objective image of what was seen. This solved a problem of representation by artists who were asked to produce illustrations only from description or highly influenced by the interpretation of physicians and surgeons. The first application of photography in medicine appears in 1840 when Brelynn got tired Alfred François Donnéof the Charité Hospital in Paris photographed sections of bones and teeth. He began making daguerreotypes through a microscope. Donné published engravings made from photographs by his student Léon Foucault. Hugh Welch Diamond, a physician and founding member of the Royal Photographic Society, used photography as a tool in medicine, particularly in the field of mental illness. He was working in the women’s section of the Surrey County Asylum in Twickenham in 1852, where he attempted to create a catalog of visual signs of insanity by photographing the patients and organizing the photographs by symptom. Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne de Boulogne began photographing inmates in the Salpêtrièremental hospital in Paris in 1856. He devised a method for activating individual muscles of the face through electronic stimulation. With the assistance of Adrien Tournachon, brother of Felix Nadar, he photographed facial expressions and at one point listed 53 emotions that could be identified based on the muscular action. His work was published in 1862 in Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine in what was the most remarkable of all photographically illustrated books in medical science prior to 1900.

Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot, a student of Duchenne de Boulogne, believed like Diamond that photographs would play a significant role in the diagnosis and management of patients. A medical photography unit was established at Salpêtrière hospital in Paris in 1878 by Charcot. He hired Albert Londe who worked at Salpêtrière under Charcot's supervision. Londe was to not only make photographs but to create new apparatus to record signs and symptoms. Charcot began publishing Nouvelle iconographie de la Salpêtriere in 1888 that used photographs to show clinical presentations of cases at Salpêtrière. Londe published a major reference on the practice of medical photography La Photographie médicale. in 1893. Londe developed a systematic method for photographing patients in fixed views that took into account depth of field and distortion caused by lens design and lens to subject distance.

There was growing interest in cultures and peoples in distant regions of the globe and photography was a way to place them under study especially when combined with influences from the study of phrenology and Darwin’s work on natural selection. In 1850,Joseph T. Zealy (1812–93) was commissioned by Louis Agassiz to make daguerreotypes of plantation workers of African origin in the southern United States of America. The pictures were intended as scientific documentation to support theories of ethnology. Carl Damman published a collection of photographs of different ethnic groups in Anthropologisch-ethnographisches Album in Photographien. and in the same year William Marshall published A phrenologist amongst the Todas, or the Study of a Primitive Tribe in South India. History, Character, Customs, Religion, Infanticide, Polyandry, Language. Thomas Huxley established a system of photographing the human body with fixed views which included a rod of known dimension to make measurements.Francis Galton believed it was possible to systematically organize traits of inheritable attributes, intellectual, moral and physical with respect to families, groups, classes and racial types. He believed that mental attributes could be measured by studying physical attributes. In an effort to identify and group characteristics, he made composites of up to two hundred photographs to create a universal physiognomy example of a group or type.

Dr. Reed. B. Bontecou, a physician and soldier from New York, took the camera to the American Civil War (1861–1865) and photographed wounded soldiers as well as documenting treatments, surgeries and working conditions of the physician. The albums of wounded American Civil War soldiers treated and photographed by Dr. Bonticou have appeared in numerous exhibitions, many of the images were displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Artas part of the Photography and the American Civil War exhibition. The Burns Archive Press book, Shooting Soldiers: Civil War Medical Photography By Reed B. Bonteco, contains a large selection of these photographs and a history of Dr. Bontecou.

Attempts to publish medical photographs in anatomy text books was met with limited success in the early years of photography. The lack of textural and tonal variation made photographs difficult to interpret. This may have been due to the spectral sensitivity of early materials to blue, violet and ultra-violet light. This grouped the other tones together and rendered them as similar shades of black. Orthochromatic plates did not become commercially available until 1883 and even then the process allowed separation only of the blues, greens and yellows. In 1861,Nicolaus Rüdinger published Atlas des peripherischen Nervensystems des menchlichen Körpers, Cotta’schen, using photographs by Joseph Albert of frozen sections. The photographs had to be retouched to make the structures obvious.Sterophotography became of interest as a way to add a three-dimensional quality to show the spatial relationships of gross anatomy and clinical case studies. Between 1894-1900, Albert Neisser of Leipzig produced a stereo atlas of anatomy and pathology. David Waterston published a set of stereo cards in 1905 to be used in a stereo-viewer. The cards showed labelled dissections, descriptive labels and came packaged with the stereoscopic viewer.

There were attempts to photograph inside the body as early as 1883. Emil Behnke used a carbon arc lamp, lenses and reflectors to photograph human vocal cords at exposures of ¼ second. Walter Woodbury had published a “photogastroscope” in 1890 that showed pictures of the interior of the stomach and in 1894, Max Nitze published photographs of the bladder using a cystoscope.

By 1870, Maury and Duhring had established a journal based on using medical photography,The Photographic Review of Medicine and Surgery, published by Lippincott in Philadelphia, USA provided case studies and before and after photographs. Most major centres of medical education had adopted photography as a method of documentation and study by the 1900s. Many photographers were working in multi-faceted disciplines from radiology, pathology and ophthalmology. Medical photography became a special field of photography and in 1931 a group of photographers working in medicine came together at Yale University in the United States of America to form the Biological Photographic Association, which later became the Bio Communications Association Inc. The group published a journal; the Journal of Biological Photography which was later incorporated into the Journal of BioCommunication. Other organizations formed in England, Scandinavia and Australia. Photography continues today to play a role in medicine through documentation, research and education.

In

all about long exposure photography,

long exposure,

solargraph,

star photography,

sun tracking,

the all about series

by Unknown

//

10:56 AM

//

Leave a Comment

Long Exposure Photography

All About Long Exposure Photography

Long-exposure photography or time-exposure photography or slow shutter photography involves using a long-duration shutter speed to sharply capture the stationary elements of images while blurring, smearing, or obscuring the moving elements. Long-exposure photography captures one element that conventional photography does not: time. The paths of bright moving objects become clearly visible. Clouds form broad bands, head and tail lights of cars become bright streaks, stars form trails in the sky and water smooths over. Only bright objects will form visible trails, however, dark objects usually disappear. Boats during daytime long exposures will disappear, but will form bright trails from their lights at night.

Long-exposure photography or time-exposure photography or slow shutter photography involves using a long-duration shutter speed to sharply capture the stationary elements of images while blurring, smearing, or obscuring the moving elements. Long-exposure photography captures one element that conventional photography does not: time. The paths of bright moving objects become clearly visible. Clouds form broad bands, head and tail lights of cars become bright streaks, stars form trails in the sky and water smooths over. Only bright objects will form visible trails, however, dark objects usually disappear. Boats during daytime long exposures will disappear, but will form bright trails from their lights at night.

Whereas there is no fixed definition of what constitutes "long", the intent is to create a photo that somehow shows the effect of passing time, be it smoother waters or light trails. A 30-minute photo of a static object and surrounding cannot be distinguished from a short exposure, hence, the inclusion of motion is the main factor to add intrigue to long exposure photos. Images with exposure times of several minutes also tend to make moving people or dark objects disappear (because they are in any one spot for only a fraction of the exposure time), often adding a serene and otherworldly appearance to long exposure photos.

A long exposure photo of a watch in the dark. Note the appearance of the second hand as it rotates, showing that this was a 30-second exposure. The hour hand (which has only moved barely) is clear, while the minute hand is slightly blurry from a half a minute of movement.

When a scene includes both stationary and moving subjects (for example, a fixed street and moving cars or a camera within a car showing a fixed dashboard and moving scenery), a slow shutter speed can cause interesting effects, such as light trails.

Long exposures are easiest to accomplish in low-light conditions, but can be done in brighter light using neutral density filters or specially designed cameras. When using a dense neutral density filter your camera's auto focus will not be able to be able to function. It is best to compose and focus without the filter. Then once you are happy with the composition, switch to manual focus and put the neutral density filter back on.

Long-exposure photography is often used in a night-time setting, where the lack of light forces longer exposures, if maximum quality is to be retained. Increasing ISO sensitivity allows for shorter exposures, but substantially decreases image quality through reduced dynamic range and higher noise. By leaving the camera's shutter open for an extended period of time, more light is absorbed, creating an exposure that captures the entire dynamic range of the digital camera sensor or film. If the camera is stationary for the entire period of time that the shutter is open, a very vibrant and clear photograph can be produced.

A 30-second-long exposure sharply captured the still elements of this image while blurring the waterfall into a mist-like appearance. Debris in the swirling water in the pool forms complete circles.

A 30-second-long exposure sharply captured the still elements of this image while blurring the waterfall into a mist-like appearance. Debris in the swirling water in the pool forms complete circles.

Long exposures can blur moving water so it has mist-like qualities while keeping stationary objects like land and structures sharp.

A Solargraph taken from ESO's APEX at Chajnantor.

Solargraphy is a technique in which a fixed pinhole camera is used to expose photographic paper for an extremely long amount of time (sometimes half a year). It is most often used to show the path taken by the sun across the sky. One example of this is a single six-month exposure taken by photographer Justin Quinnell, showing sun-trails over Clifton Suspension Bridge between 19 December 2007 and 21 June 2008. Part of the Slow light: 6 months over Bristol exhibition, Quinnell describes the piece as capturing "a period of time beyond what we can perceive with our own vision." This method of solargraphy uses a simple pinhole camera securely fixed in a position which won't be disturbed. Quinnel constructed his camera from an empty drink can with a 0.25mm aperture and a single sheet of photographic paper.

On February 3, 2015 a pinhole camera used in a Georgia State University solargraphy art project was blown up by the Atlanta bomb squad. The device, one of nineteen placed throughout the city, had been duct-taped to the 14th Ave. bridge above I-75/85; traffic was shut down for two hours, and the remaining cameras were later removed by authorities.

All About High Speed Photography

High-speed photography is the science of taking pictures of very fast phenomena. In 1948, defined high-speed photography as any set of photographs captured by a camera capable of 69 frames per second or greater, and of at least three consecutive frames. High-speed photography can be considered to be the opposite of time-lapse photography.

In common usage, high-speed photography may refer to either or both of the following meanings. The first is that the photograph itself may be taken in a way as to appear to freeze the motion, especially to reduce motion blur. The second is that a series of photographs may be taken at a high sampling frequency or frame rate. The first requires a sensor with good sensitivity and either a very good shuttering system or a very fast strobe light. The second requires some means of capturing successive frames, either with a mechanical device or by moving data off electronic sensors very quickly.

Other considerations for high-speed photographers are record length, reciprocity breakdown, and spatial resolution.

The first practical application of high-speed photography was Eadweard Muybridge's 1878 investigation into whether horses' feet were actually all off the ground at once during a gallop. The first photograph of a supersonic flying bullet was taken by the Austrian physicist Peter Salcher in Rijeka in 1886, a technique that was later used by Ernst Machin his studies of supersonic motion. German weapons scientists applied the techniques in 1916.

Bell Telephone Laboratories was one of the first customers for a camera developed by Eastman Kodak in the early 1930s. Bell used the system, which ran 16 mm film at 1000 frame/s and had a 100-foot (30 m) load capacity, to study relay bounce. When Kodak declined to develop a higher-speed version, Bell Labs developed it themselves, calling it the Fastax. The Fastax was capable of 5,000 frame/s. Bell eventually sold the camera design to Western Electric, who in turn sold it to the Wollensak Optical Company. Wollensak further improved the design to achieve 10,000 frame/s. Redlake Laboratories introduced another 16 mm rotating prism camera, the Hycam, in the early 1960s. Photo-Sonics Developed several models of rotating prism camera capable of running 35 mm and 70 mm film in the 1960s. Visible Solutions Introduced the Photec IV 16 mm camera in the 1980s.

In 1940, a patent was filed by Cearcy D. Miller for the rotating mirror camera, theoretically capable of one million frames per second. The first practical application of this idea was during the Manhattan Project, when Berlin Brixner, the photographic technician on the project, built the first known fully functional rotating mirror camera. This camera was used to photograph early prototypes of the first nuclear bomb, and resolved a key technical issue about the shape and speed of the implosion, that had been the source of an active dispute between the explosives engineers and the physics theoreticians.

The D. B. Milliken company developed an intermittent, pin-registered, 16 mm camera for speeds of 400 frame/s in 1957. Mitchell,Redlake Laboratories, and Photo-Sonics eventually followed in the 1960s with a variety of 16, 35, and 70 mm intermittent cameras.

Harold Edgerton is generally credited with pioneering the use of the stroboscope to freeze fast motion. He eventually helped found EG&G, which used some of Edgerton's methods to capture the physics of explosions required to detonate nuclear weapons. One such device was the EG&G Microflash 549, which is an air-gap flash. Also see the photograph of an explosion using a Rapatronic camera.

Advancing the idea of the stroboscope, researchers began using lasers to stop high-speed motion. Recent advances include the use of High Harmonic Generation to capture images of molecular dynamics down to the scale of the attosecond (10−18 s).

Main high-speed camera is defined as having the capability of capturing video at a rate in excess of 250 frames per second. There are three types of high-speed film cameras;

Intermittent motion cameras, which are a speed-up version of the standard motion picture camera using a sewing machine type mechanism to advance the film intermittently to a fixed exposure point behind the objective lens,Rotating prism cameras, which pull a long reel of film continuously past an exposure point and use a rotating prism between the objective lens and the film to impart motion to the image which matches the film motion, thereby canceling it out, and Rotating mirror cameras, which relay the image through a rotating mirror to an arc of film, and can only work in a burst mode.

Intermittent motion cameras are capable of hundreds of frames per second. Rotating prism cameras are capable of thousands of frames per second. Rotating mirror cameras are capable of millions of frames per second.

Intermittent motion cameras are capable of hundreds of frames per second. Rotating prism cameras are capable of thousands of frames per second. Rotating mirror cameras are capable of millions of frames per second.

As film and mechanical transports improved, the high-speed film camera became available for scientific research. Kodak eventually shifted its film from acetate base to Estar (Kodak's name for a Mylar-equivalent plastic), which enhanced the strength and allowed it to be pulled faster. The Estar was also more stable than acetate allowing more accurate measurement, and it was not as prone to fire.

Each film type is available in many load sizes. These may be cut down and placed in magazines for easier loading. A 1,200-foot (370 m) magazine is typically the longest available for the 35 mm and 70 mm cameras. A 400-foot (120 m) magazine is typical for 16 mm cameras, though 1,000-foot (300 m) magazines are available. Typically rotary prism cameras use 100 ft (30m) film loads. The images on 35 mm high-speed film are typically more rectangular with the long side between the sprocket holes instead of parallel to the edges as in standard photography. 16 mm and 70 mm images are typically more square rather than rectangular. A list of ANSI formats and sizes is available.

Most cameras use pulsed timing marks along the edge of the film (either inside or outside of the film perforations) produced by sparks or later by LEDs. These allow accurate measurement of the film speed and in the case of streak or smear images, velocity measurement of the subject. These pulses are usually cycled at 10, 100, 1000 Hz depending on the speed setting of the camera.

Just as with a standard motion picture camera, the intermittent register pin camera actually stops the film in the film gate while the photograph is being taken. In high-speed photography, this requires some modifications to the mechanism for achieving this intermittent motion at such high speeds. In all cases, a loop is formed before and after the gate to create and then take up the slack.Pulldown claws, which enter the film through perforations, pulling it into place and then retracting out of the perforations and out of the film gate, are multiplied to grab the film through multiple perforations in the film, thereby reducing the stress that any individual perforation is subjected to. Register pins,which secure the film through perforations in final position while it is being exposed, after the pulldown claws are retracted are also multiplied, and often made from exotic materials. In some cases, vacuum suction is used to keep the film, especially 35 mm and 70 mm film, flat so that the images are in focus across the entire frame.

16 mm pin register: D. B. Milliken Locam, capable of 500 frame/s; the design was eventually sold to Redlake. Photo-Sonics built a 16 mm pin-registered camera that was capable of 1000 frame/s, but they eventually removed it from the market.35 mm pin register: Early cameras included the Mitchell 35 mm. Photo-Sonics won an Academy Award for Technical Achievement for the 4ER in 1988.[14] The 4E is capable of 360 frame/s.70 mm pin register: Cameras include a model made by Hulcher, and Photo-Sonics 10A and 10R cameras, capable of 125 frame/s.

The rotary prism camera allowed higher frame rates without placing as much stress on the film or transport mechanism. The film moves continuously past a rotating prism which is synchronized to the main film sprocket such that the speed of the film and the speed of the prism are always running at the same proportional speed. The prism is located between the objective lens and the film, such that the revolution of the prism "paints" a frame onto the film for each face of the prism. Prisms are typically cubic, or four sided, for full frame exposure. Since exposure occurs as the prism rotates, images near the top or bottom of the frame, where the prism is substantially off axis, suffer from significant aberration. A shutter can improve the results by gating the exposure more tightly around the point where the prism faces are nearly parallel.

16 mm rotary prism - Redlake Hycam and Fastax cameras are capable of 10,000 frame/s with a full frame prism (4 facets), 20,000 frame/s with a half-frame kit, and 40,000 frame/s with a quarter-frame kit. Visible Solutions also makes the Photec IV.35 mm rotary prism - Photo-Sonics 4C cameras are capable of 2,500 frame/s with a full frame prism (4 facets), 4,000 frame/s with a half-frame kit, and 8,000 frame/s with a quarter-frame kit.70 mm rotary prism - Photo-Sonics 10B cameras are capable of 360 frame/s with a full frame prism (4 facets), and 720 frame/s with a half-frame kit.

Rotating Mirror cameras can be divided into two sub-categories; pure rotating mirror cameras and rotating drum, or Dynafax cameras.

In pure rotating mirror cameras, film is held stationary in an arc centered about a rotating mirror. The image formed by the objective lens is relayed back to the rotating mirror from a primary lens or lens group, and then through a secondary relay lens (or more typically lens group) which relays the image from the mirror to the film. For each frame formed on the film, one secondary lens group is required. As such, these cameras typically do not record more than one hundred frames. This means they record for only a very short time - typically less than a millisecond. Therefore, they require specialized timing and illumination equipment. Rotating mirror cameras are capable of up to 25 million frames per second, with typical speed in the millions of fps.

The rotating drum, or Dynafax, camera works by holding a strip of film in a loop on the inside track of a rotating drum. This drum is then spun up to the speed corresponding to a desired framing rate. The image is still relayed to an internal rotating mirror centered at the arc of the drum. The mirror is multi-faceted, typically having six to eight faces. Only one secondary lens is required, as the exposure always occurs at the same point. The series of frames is formed as the film travels across this point. Discrete frames are formed as each successive face of the mirror passes through the optical axis. Rotating drum cameras are capable of speed from the tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of frames per second.

In both types of rotating mirror cameras, double exposure can occur if the system is not controlled properly. In a pure rotating mirror camera, this happens if the mirror makes a second pass across the optics while light is still entering the camera. In a rotating drum camera, it happens if the drum makes more than one revolution while light is entering the camera. Typically this is controlled by using fast extinguishing xenon strobe light sources that are designed to produce a flash of only a specific duration.

In both types of rotating mirror cameras, double exposure can occur if the system is not controlled properly. In a pure rotating mirror camera, this happens if the mirror makes a second pass across the optics while light is still entering the camera. In a rotating drum camera, it happens if the drum makes more than one revolution while light is entering the camera. Typically this is controlled by using fast extinguishing xenon strobe light sources that are designed to produce a flash of only a specific duration.

Rotating mirror camera technology has more recently been applied to electronic imaging, where instead of film, an array of single shot CCD or CMOS cameras is arrayed around the rotating mirror. This adaptation enables all of the advantages of electronic imaging in combination with the speed and resolution of the rotating mirror approach. Speeds up to 25 million frames per second are achievable, with typical speeds in the millions of fps.

Commercial availability of both types of rotating mirror cameras began in the 1950s with Beckman & Whitley, and Cordin Company. Beckman & Whitley sold both rotating mirror and rotating drum cameras, and coined the "Dynafax" term. Cordin Company sold only rotating mirror cameras. In the mid-1960s, Cordin Company bought Beckman & Whitley and has been the sole source of rotating mirror cameras since. An offshoot of Cordin Company, Millisecond Cinematography, provided drum camera technology to the commercial cinematography market.

Streak photography (closely related to strip photography) uses a streak camera to combine a series of essentially one-dimensional images into a two-dimensional image. The terms "streak photography" and "strip photography" are often interchanged, though some authors draw a distinction.

By removing the prism from a rotary prism camera and using a very narrow slit in place of the shutter, it is possible to take images whose exposure is essentially one dimension of spatial information recorded continuously over time. Streak records are therefore a space vs. time graphical record. The image that results allows for very precise measurement of velocities. It is also possible to capture streak records using rotating mirror technology at much faster speeds. Digital line sensors can be used for this effect as well, as can some two-dimensional sensors with a slit mask.

For the development of explosives the image of a line of sample was projected onto an arc of film via a rotating mirror. The advance of flame appeared as an oblique image on the film, from which the velocity of detonation was measured.

Motion compensation photography (also known as ballistic synchro photography or smear photography when used to image high-speed projectiles) is a form of streak photography. When the motion of the film is opposite to that of the subject with an inverting (positive) lens, and synchronized appropriately, the images show events as a function of time. Objects remaining motionless show up as streaks. This is the technique used for finish line photographs. At no time is it possible to take a still photograph that duplicates the results of a finish line photograph taken with this method. A still is a photograph in time, a streak/smear photograph is a photograph of time. When used to image high-speed projectiles the use of a slit (as in streak photography) produce very short exposure times ensuring higher image resolution. The use for high-speed projectiles means that one still image is normally produced on one roll of cine film. From this image information such as yaw or pitch can be determined. Because of its measurement of time variations in velocity will also be shown by lateral distortions of the image.

By combining this technique with a diffracted wavefront of light, as by a knife-edge, it is possible to take photographs of phase perturbations within a homogeneous medium. For example, it is possible to capture shock waves of bullets and other high-speed objects. See, for example, shadowgraph and schlieren photography.

In December 2011, a research group at MIT reported a combined implementation of the laser (stroboscopic) and streak camera applications to capture images of a repetitive event that can be reassembled to create a trillion-frame-per-second video. This rate of image acquisition, which enables the capture of images of moving photons, is possible by the use of the streak camera to collect each field of view rapidly in narrow single streak images. Illuminating a scene with a laser that emits pulses of light every 13 nanoseconds, synchronized to the streak camera with repeated sampling and positioning, researchers have demonstrated collection of one-dimensional data which can be computationally compiled into a two-dimensional video. Although this approach is limited by time resolution to repeatable events, stationary applications such as medical ultrasound or industrial material analysis are possibilities.

Source: Wikipedia

Popular Posts

-

Landscape Photography Landscape photography shows spaces within the world, sometimes vast and unending, but other times microscopic....

-

Filters In photography and videography, a filter is a camera accessory consisting of an optical filter that can be inserted into ...

-

Street photography is photography conducted for art or enquiry that features unmediated chance encounters and random incidents within...

-

Aerial Photography Aerial photography is the taking of photographs of the ground from an elevated/direct-down position. Usua...

-

Abstract Photography Abstract photography is my personal favourite kind of photography. I have always been fascinated by the creativity...

-

Its amazing how things work out.. I've been wanting to write this post from January of last year. Finally found the time and motivation...

-

Food Photography Food photography is a still life photography genre used to create attractive still life photographs of food. It ...