Saturday, May 7, 2016

In

documentary photography,

how to do documentary,

journalism,

photojournalism

by Unknown

//

11:39 AM

//

Leave a Comment

All About Documentary Photography

Documentary Photography

Documentary photography usually refers to a popular form of photography used to chronicle events or environments both significant and relevant to history and historical events and everyday life. It is typically covered in professional photojournalism, or real life reportage, but it may also be an amateur, artistic, or academic pursuit.

The term document applied to photography antedates the mode or genre itself. Photographs meant to accurately describe otherwise unknown, hidden, forbidden, or difficult-to-access places or circumstances. The earliest daguerreotype and calotype "surveys" of the ruins of the Near East, Egypt, and the American wilderness areas. Nineteenth-century archaeologist John Beasly Greene, for example, traveled to Nubia in the early 1850s to photograph the major ruins of the region; One early documentation project was the French Missions Heliographiques organized by the official Commission des Monuments historiques to develop an archive of France's rapidly disappearing architectural and human heritage; the project included such photographic luminaries as Henri Le Secq,Edouard Denis Baldus, and Gustave Le Gray.

In the United States, photographs tracing the progress of the American Civil War (1861-1865) by photographers for at least three consortia of photographic publisher-distributors, most notably Mathew Brady andAlexander Gardner, resulted in a major archive of photographs ranging from dry records of battle sites to harrowing images of the dead by Timothy O'Sullivan and evocative images by George N. Barnard. A huge body of photography of the vast regions of the Great West was produced by official government photographers for the Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories (a predecessor of the USGS), during the period 1868–1878, including most notably the photographers Timothy O'Sullivan and William Henry Jackson.

Both the Civil War and USGS photographic works point up an important feature of documentary photography: the production of an archive of historical significance, and the distribution to a wide audience through publication. The US Government published Survey photographs in the annual Reports, as well as portfolios designed to encourage continued funding of scientific surveys.

The development of new reproduction methods for photography provided impetus for the next era of documentary photography, in the late 1880s and 1890s, and reaching into the early decades of the 20th century. This period decisively shifted documentary from antiquarian and landscape subjects to that of the city and its crises. The refining of photo gravure methods, and then the introduction of halftone reproduction around 1890 made low cost mass-reproduction in newspapers, magazines and books possible. The figure most directly associated with the birth of this new form of documentary is the journalist and urban social reformer Jacob Riis. Riis was a New York police-beat reporter who had been converted to urban social reform ideas by his contact with medical and public-health officials, some of whom were amateur photographers. Riis used these acquaintances at first to gather photographs, but eventually took up the camera himself. His books, most notably How the Other Half Lives of 1890 and The Children of the Slums of 1892, used those photographs, but increasingly he also employed visual materials from a wide variety of sources, including police "mug shots" and photojournalistic images.

Riis's documentary photography was passionately devoted to changing the inhumane conditions under which the poor lived in the rapidly expanding urban-industrial centers. His work succeeded in embedding photography in urban reform movements, notably the Social Gospel and Progressivemovements. His most famous successor was the photographer Lewis Wickes Hine, whose systematic surveys of conditions of child-labor in particular, made for the National Child Labor Commission and published in sociological journals like The Survey, are generally credited with strongly influencing the development of child-labor laws in New York and the United States more generally.

In 1900, Englishwoman Alice Seeley Harristraveled to the Congo Free State with her husband, John Hobbis Harris (a missionary). There she photographed Belgian atrocities against local people with an early Kodak Brownie camera. The images were widely distributed through magic lantern screenings and were critical in changing public perceptions of slavery and eventually forcingLeopold II of Belgium to cede control of the territory to the Belgian government, creating the Belgian Congo.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression brought a new wave of documentary, both of rural and urban conditions. The Farm Security Administration, a common term for the Historical Division, supervised by Roy Stryker, funded legendary photographic documentarians, including Walker Evans,Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, John Vachon, and Marion Post Wolcott among others. This generation of documentary photographers is generally credited for codifying the documentary code of accuracy mixed with impassioned advocacy, with the goal of arousing public commitment to social change.

During the wartime and postwar eras, documentary photography increasingly became subsumed under the rubric of photo journalism. Swiss-American photographer Robert Frank is generally credited with developing a counterstrain of more personal, evocative, and complex documentary, exemplified by his work in the 1950s, published in the United States in his 1959 book, The Americans. In the early 1960s, his influence on photographers like Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander resulted in an important exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which brought those two photographers together with their colleagueDiane Arbus under the title, New Documents. MoMA curator John Szarkowski proposed in that exhibition that a new generation, committed not to social change but to formal and iconographical investigation of the social experience of modernity, had replaced the older forms of social documentary photography.

In the 1970s and 1980s, a spirited attack on traditional documentary was mounted by historians, critics, and photographers. One of the most notable was the photographer-criticAllan Sekula, whose ideas and the accompanying bodies of pictures he produced, influenced a generation of "new new documentary" photographers, whose work was philosophically more rigorous, often more stridently leftist in its politics. Sekula emerged as a champion of these photographers, in critical writing and editorial work. Notable among this generation are the photographers Fred Lonidier, whose 'Health and Safety Game" of 1976 became a model of post-documentary, and Martha Rosler, whose "The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems" of 1974-75 served as a milestone in the critique of classical humanistic documentary as the work of privileged elites imposing their visions and values on the dis-empowered.

Since the late 1990s, an increased interest in documentary photography and its longer term perspective can be observed. Nicholas Nixonextensively documented issues surrounded by American life. South African documentary photographer Pieter Hugo engaged in documenting art traditions with a focus on African communities. Antonin Kratochvilphotographed a wide variety of subjects, including Mongolia's street children for the Museum of Natural History. Fazal Sheikhsought to reflect the realities of the most underprivileged peoples of different third world countries.

Documentary photography generally relates to longer term projects with a more complex story line, while photojournalism concerns more breaking news stories. The two approaches often overlap.

Since the late 1970s, the decline of magazine published photography meant traditional forums for such work were vanishing. Many documentary photographers have now focused on the art world and galleries of a way of presenting their work and making a living. Traditional documentary photography has found a place in dedicated photography galleries alongside other artists working in painting, sculpture and modern media.

Source: wikipedia

All About Abstract Photography

Abstract Photography

Abstract photography is my personal favourite kind of photography. I have always been fascinated by the creativity involved in each abstract photograph. it gives a whole new meaning and lets you see the world from a different PERSPECTIVE.

Abstract photography, sometimes called non-objective, experimental, conceptual or concrete photography, is a means of depicting a visual image that does not have an immediate association with the object world and that has been created through the use of photographic equipment, processes or materials. An abstract photograph may isolate a fragment of a natural scene in order to remove its inherent context from the viewer, it may be purposely staged to create a seemingly unreal appearance from real objects, or it may involve the use of color, light, shadow, texture, shape and/or form to convey a feeling, sensation or impression. The image may be produced using traditional photographic equipment like a camera, darkroom or computer, or it may be created without using a camera by directly manipulating film, paper or other photographic media, including digital presentations.

Abstract photography, sometimes called non-objective, experimental, conceptual or concrete photography, is a means of depicting a visual image that does not have an immediate association with the object world and that has been created through the use of photographic equipment, processes or materials. An abstract photograph may isolate a fragment of a natural scene in order to remove its inherent context from the viewer, it may be purposely staged to create a seemingly unreal appearance from real objects, or it may involve the use of color, light, shadow, texture, shape and/or form to convey a feeling, sensation or impression. The image may be produced using traditional photographic equipment like a camera, darkroom or computer, or it may be created without using a camera by directly manipulating film, paper or other photographic media, including digital presentations.

There has been no commonly-used definition of the term "abstract photography". Books and articles on the subject include everything from a completely representational image of an abstract subject matter, such as Aaron Siskind's photographs of peeling paint, to entirely non-representational imagery created without a camera or film, such as Marco Breuer's fabricated prints and books. The term is both inclusive of a wide range of visual representations and explicit in its categorization of a type of photography that is visibly ambiguous by its very nature.

Many photographers, critics, art historians and others have written or spoken about abstract photography without attempting to formalize a specific meaning. Alvin Langdon Coburn in 1916 proposed that an exhibition be organized with the title "Abstract Photography", for which the entry form would clearly state that "no work will be admitted in which the interest of the subject matter is greater than the appreciation of the extraordinary." The proposed exhibition did not happen, yet Coburn later created some distinctly abstract photographs.

Photographer and Professor of Psychology John Suler, in his essay Photographic Psychology: Image and Psyche, said that "An abstract photograph draws away from that which is realistic or literal. It draws away from natural appearances and recognizable subjects in the actual world. Some people even say it departs from true meaning, existence, and reality itself. It stands apart from the concrete whole with its purpose instead depending on conceptual meaning and intrinsic form....Here’s the acid test: If you look at a photo and there’s a voice inside you that says 'What is it?'….Well, there you go. It’s an abstract photograph."

Barbara Kasten, also a photographer and professor, wrote that "Abstract photography challenges our popular view of photography as an objective image of reality by reasserting its constructed nature....Freed from its duty to represent, abstract photography continues to be a catchall genre for the blending of mediums and disciplines. It is an arena to test photography."

German photographer and photographic theorist Gottfried Jäger used the term "concrete photography", playing off the term "concrete art", to describe a particular kind of abstract photography. He said:

"Concrete photography does not depict the visible (like realistic or documentary photography);It does not represent the non-visible (like staged, depictive photography);It does not take recourse to views (like image-analytical, conceptual, demonstrative photography).Instead it establishes visibility. It is only visible, the only-visible.In this way it abandons its media character and gains object character."

More recently conceptual artist Mel Bochnerhand wrote a quote from the Encyclopedia Britannia that said "Photography cannot record abstract ideas." on a note card, then photographed it and printed it using six different photographic processes. He turned the words, the concept and the visualization of the concept into art itself, and in doing so created a work that presented yet another type of abstract photography, again without ever defining the term itself.

Some of the earliest images of what may be called abstract photography appeared within the first decade after the invention of the craft. In 1842 John William Draper created images with a spectroscope, which dispersed light rays into a then previously unrecorded visible pattern. The prints he made had no reference to the reality of the visible world that other photographers then recorded, and they demonstrated photography's unprecedented ability to transform what had previously been invisible into a tangible presence. Draper saw his images as science records rather than art, but their artistic quality is appreciated today for their groundbreaking status and their intrinsic individuality.

Another early photographer, Anna Atkins in England, produced a self-published book ofphotograms made by placing dried algaedirectly on cyanotype paper. Intended as a scientific study, the stark white on blue images have an ethereal abstract quality due to the negative imaging and lack of natural context for the plants.

The discovery of the X-ray in 1895 andradioactivity in 1896 caused a great public fascination with things that were previously invisible or unseen. In response, photographers began to explore how they could capture what could not been seen by normal human vision.

About this same time Swedish author and artist August Strindberg experimented with subjecting saline solutions on photographic plates to heat and cold. The images he produced with these experiments were indefinite renderings of what could not otherwise be seen and were thoroughly abstract in their presentation.

Near the turn of the century Louis Darget in France tried to capture images of mental processes by pressing unexposed plates to the foreheads of sitters and urging them to project images from their minds onto the plates. The photographs he produced were blurry and indefinite, yet Darget was convinced that what he called "thought vibrations" were indistinguishable from light rays.

Near the turn of the century Louis Darget in France tried to capture images of mental processes by pressing unexposed plates to the foreheads of sitters and urging them to project images from their minds onto the plates. The photographs he produced were blurry and indefinite, yet Darget was convinced that what he called "thought vibrations" were indistinguishable from light rays.

During the first decade of the 20th century there was a wave of artistic exploration that hastened the transition in painting and sculpture from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism to Cubism and Futurism. Beginning in 1903 a series of annual art exhibitions in Paris called the Salon d'Automne introduced the public to then radical vision of artists like Cézanne, Picasso,Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, František Kupka, and Albert Gleizes. Jean Metzinger. A decade later the Armory Show in New York created a scandal by showing completely abstract works by Kandinsky, Braque,Duchamp, Robert Delaunay and others.

The public's interest in and sometimes repulsion to abstract art was duly noted by some of the more creative photographers of the period. By 1910, in New York Alfred Stieglitz began to show abstract painters likeMarsden Hartley and Arthur Dove at his 291 art gallery, which had previously exhibited onlypictorial photography. Photographers like Stieglitz, Paul Strand and Edward Steichen all experimented with depictive subjects photographed in abstract compositions.

The first publicly exhibited images that are now recognized as abstract photographs were a series called Symmetrical Patterns from Natural Forms, shown by Erwin Quedenfeldt in Cologne in 1914. Two years later Alvin Langdon Coburn began experimenting with a series he calledVortographs. During one six-week period in 1917 he took about two dozen photographs with a camera outfitted with a multi-faceted prism. The resulting images were purposely unrelated to the realities he saw and to his previous portraits and cityscapes. He wrote "Why should not the camera throw off the shackles of contemporary representations…? Why, I ask you earnestly, need we go on making commonplace little exposures…?"

In the 1920s and 1930s there was a significant increase in the number of photographers who explored abstract imagery. In Europe, Prague became a center of avant-garde photography, with František Drtikol, Jaroslav Rössler, Josef Sudek andJaromír Funke all creating photographs influenced by Cubism and Futurism. Rössler's images in particular went beyond representational abstraction to pure abstractions of light and shadow.

In Germany and later in the U.S. László Moholy-Nagy, a leader of the Bauhaus school of modernism, experimented with the abstract qualities of the photogram. He said that "the most astonishing possibilities remain to be discovered in the raw material of photograph" and that photographers "must learn to seek, not the 'picture,' not the esthetic of tradition, but the ideal instrument of expression, the self-sufficient vehicle for education."

Some photographers during this time also pushed the boundaries of conventional imagery by incorporating the visions ofsurrealism or futurism into their work. Man Ray, Maurice Tabard, André Kertész, Curtis Moffat and Filippo Masoero were some of the best known artists who produced startling imagery that questioned both reality and perspective.

Both during and after World War IIphotographers such as Minor White, Aaron Siskind, Henry Holmes Smith and Lotte Jacobiexplored compositions of found objects in ways that demonstrated even our natural world has elements of abstraction embedded in it.

Frederick Sommer broke new ground in 1950 by photographing purposely rearranged found objects, resulting in ambiguous images that could be widely interpreted. He chose to title one particular enigmatic image The Sacred Wood, after T.S. Eliot's essay on criticism and meaning.

The 1960s were marked uninhibited explorations in to the limits of photographic media at the time,starting with photographers who assembled or re-assembled their own and/or found images, such as Ray K. Metzker,Robert Heinecken and Walter Chappell.

Beginning in the late 1970s photographers stretched the limits of both scale and surface in what was then traditional photographic media that had to be developed in a darkroom. Inspired by the work of Moholy-Nagy, Susan Rankaitis first began embedding found images from scientific textbooks into large-scale photograms, creating has been called "a palimpsest that has to be explored almost like an archeological excavation." Later she produced enormous interactive gallery constructions that expanded the physical and conceptual notions of what a photograph might be. Her work was said to "mimic the fragmentation of the contemporary mind."

By the 1990s a new wave of photographers were exploring the possibilities of using computers to create new ways of creating photographs. Photographers such as Thomas Ruff, Barbara Kasten, Tom Friedman, andCarel Balth were creating works that combined photography, sculpture, printmaking and computer-generate images.

Once computers and photography software became widely available, the boundaries of abstract photography were expanded beyond the limits of film and chemistry into almost limitless dimensions. Any boundaries that remained between pure artists and pure photographers were eliminated by individual who worked exclusively in photography but produced only computer-generated images. Among the most well-known of the early 21st century generation were Penelope Umbrico,Ellen Carey, Nicki Stager, Shirine Gill,Wolfgang Tillmans and Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin.

source: Wikipeida

Sunday, May 1, 2016

In

birth of portraits,

famous photographers,

female photographer,

queen of black and white protraits,

Sally Mann

by Unknown

//

12:26 PM

//

Leave a Comment

One Of The a best Female Photographers

In this blog, I thought of concentrating on the amazing female talent. She is possibly the most definitive photographers to have ever lived and she is famous for her black and white portraits.

Sally Mann is an American photographer, best known for her large black-and-white photographs—at first of her young children, then later of landscapes suggesting decay and death.

After graduation, Mann worked as a photographer at Washington and Lee University. In the mid-1970s she photographed the construction of its new law school building, the Lewis Hall (now the Sydney Lewis Hall), leading to her first one-woman exhibition in late 1977 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Those surrealistic images were subsequently included as part of her first book, Second Sight, published in 1984. While Mann explored a variety of genres as she was maturing in the 1970s, she truly found her trade with her second publication, At Twelve: Portraits of Young Women (Aperture, 1988).

Her second collection, At Twelve: Portraits of Young Women, published in 1988, stimulated minor controversy. The images “captured the confusing emotions and developing identities of adolescent girls [and the] expressive printing style lent a dramatic and brooding mood to all of her images.”In the preface to the book, Ann Beattie says “when a girl is twelve years old, she often wants – or says she wants – less involvement with adults. […] [it is] a time in which the girls yearn for freedom and adults feel their own grip on things becoming a little tenuous, as they realize that they have to let their children go.” Beattie says that Mann’s photographs don’t “glamorize the world, but they don’t make it into something more unpleasant than it is, either.” The girls photographed in this series are shown “vulnerable in their youthfulness” but Mann instead focuses on the strength that the girls possess.

In an image from the book, Mann says that the young girl was extremely reluctant to stand closer to her mother’s boyfriend. Mann said that she thought it was strange because “it was their peculiar familiarity that had provoked this photograph in the first place.” Mann didn’t want to crop out the girl’s elbow but the girl refused to move in closer. According to Mann, the girl’s mother shot her boyfriend in the face with a .22 several months later. In court the mother “testified that while she worked nights at a local truck stop he was ‘at home partying and harassing my daughter.’ Mann said “the child put it to me somewhat more directly.” Mann says that she now looks at this photograph with “a jaggy chill of realization.”

Many of her other photographs containing her nude or hurt children caused controversy. For example, in "The Perfect Tomato," (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/8/83/%22The_Perfect_Tomato%22_by_Sally_Mann_%281990%29_%28correct_image%29.jpg) the viewer sees a nude Jessie, posing on a picnic table outside, bathed in light. Jessie told Steven Cantor during the filming of one of his movies that she had just been playing around and her mother told her to freeze, and she tried to capture the image in a rush because the sun was setting. This explains why everything is blurred except for the tomato, hence the photograph's title. This image was likely criticized for Jessie’s nudity and presentation of the adolescent female form. While Jessie was aware of this photograph, Dana Cox, in her essay, said that the Mann children were probably unaware of the other photographs being taken as Mann’s children were often naked because “it came natural to them.”This habit of nudity is a family thing because Mann says she used to walk around her house naked when she was growing up. Cox states that “the own artist’s childhood is reflected in the way she captures moments in her children’s lives.” One image that deals more with another aspect of childhood besides "naked play", Jessie's Cut, shows Jessie's head, wrapped in what appears to be plastic, with blood running down the side of her face from the cut above her left eye. The cut is stitched and the blood is dry and stains her skin. As painful as the image looks, there are a great number of viewers who could relate to Jessie when they think about the broken bones and stitched up cuts they had during childhood.

When Time magazine named her “America’s Best Photographer” in 2001, it wrote:

"Mann recorded a combination of spontaneous and carefully arranged moments of childhood repose and revealingly — sometimes unnervingly — imaginative play. What the outraged critics of her child nudes failed to grant was the patent devotion involved throughout the project and the delighted complicity of her son and daughters in so many of the solemn or playful events. No other collection of family photographs is remotely like it, in both its naked candor and the fervor of its maternal curiosity and care."

Mann received an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from the Corcoran Museum in May 2006. The Royal Photographic Society (UK) awarded her an Honorary Fellowship in 2012.

Mann won the 2016 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction for Hold Still: A Memoir in Photographs.

Friday, April 29, 2016

In

Ansel Easton Adams,

birth of creative photography,

famous photographers,

photography legend,

SLR,

the world of photography

by Unknown

//

1:11 PM

//

1 comment

Possibly the best photographer to walk the face of the earth

This is a story about Ansel Easton Adams. possibly the best photographer ever. Ansel Easton Adams was an American photographer and an environmentalist. he is famously known for his blak and white landscape photographs of the american west, especially Yosemite national park have been widely reproduced on calenders, posters and books. with Fred Archer, Ansel Easton Adams developed the Zone system as a way to determine proper exposure and adjust the contrast of the final print. the resulting clarity and depth characterized his photographs. Ansel Easton Adams primarily used large format cameras because their high resolution helped ensure sharpness in his image.

Ansel Easton Adams founded the photography group known as group f/64 along with photographers Willard Van Dyke and Edward Weston.

Ansel Easton Adams was born in the western addition of San Francisco, California, to Charles Hitchcock and Olive Bray Adams. An only child, he was named after his uncle Ansel Easton. his mother's family came from Baltimore. The Adams family came from new England. his parental grandfather founded and built a prosperous lumbar business, which his father later ran, through his father's natural talents lay more with sciences than with business. later is life, Adams would condemn that very dame industry for cutting down many of the great redwood forests.

In 1903, his family moved 2 miles west to a new home near the seacliff neighbourhood, just south of the presido army base. the home had a splendid view of the golden gate and the marine headlands. San Francisco was devastated by the april 18, 1906 earth quake. uninjured in the initial shaking, the four year old Ansel Easton Adams was tossed face first `into a garden wall during an aftershock three hours later, breaking and scarring his nose. Among his earliest memories was watching the smoke from the ensuring fire that destroyed much of the city a few miles to the east. although a doctor recommended that his nose be reset once he reached maturity, Ansel Easton Adams's nose remained crooked his entire life.

Ansel Easton Adams was a hyperactive child and prone to frequent sickness and hypochondria. he had a few friends, but his family home and surroundings on the heights facing the golden gate provided ample childhood activities. although he had no patience for games or sports, the curious child took to the beauty of the nature at an early age, collecting bugs and exploring lobos creek and all the way to baker beach and the sea cliffs leading to lands end.

His father bought a three inch telescope and they enthusiastically shared the hobby of amateur astronomy, visiting the lick observatory on mount hamilton together. his father went on to serve as the paid secretary-treasurer of the astronomical society of the pacific from 1925 to 1950.

After the death of Ansel's grandfather and the aftermath of the panic of 1907, his father;s business suffered great financial losses, some of the induced near-poverty was because Ansel's uncle Ansel Easton and Cedric Wright's father, George Wright, had secretly sold their shares of the company to the hawaiian sugar trust for a large amount of money. by 1912, the family's standard of living dropped sharply. after young Ansel was dismissed from several private school for his restlessness adn inattentiveness, his father decided to pull him out of school in 1915, at the age of 12. Adams was then educated by private tutors, his aunt Mary, and by his father. his aunt was a follower of Robert G Ingersoll, a 19th century agnostic, abolitionist and women's suffrage advocate. as a result of his aunt's influence, Robert's teachings were important to Ansel's upbringing.

His father raised him to follow the ideas of Ralph Waldo Emerson. "to live a modest, mortal life guided by a social responsibility to man and to nature." Adams had a warm adn supportive relationship with his father, but had a distant relationship with his mother, who did not approve of his interest in photography. the day after his mother's death on 1950, Ansel had a dispute with the undertaker when choosing which casket his mother would be buried in, Ansel chose the cheapest in the room, a $260 casket that seemed the least he could purchase without doing the job himself. when the undertaker remarked, "have you no respect for the dead?" Adams replied, "one more crack like that and i will take mama elsewhere."

Adams became interested in piano at the age 12. Music became the main focus of his youth. his father sent him to a piano teacher MArie Butler, who focused on perfectionism and accuracy. after four years of studying under her guidance, adams moved on to other teachers, one being composer Henry Cowell. for the next twelve years, the piano was Adam's primary occupation and by 1920, his intended profession. although he ultimately gave up music for photography, the piano bought substance, discipline and structure to his frustrating and erratic youth. moreover the careful training and exact craft required of a musician profoundly informed his visual artistry, as well as his influential writings and teachings on photography.

Ansel Easton Adams founded the photography group known as group f/64 along with photographers Willard Van Dyke and Edward Weston.

Ansel Easton Adams was born in the western addition of San Francisco, California, to Charles Hitchcock and Olive Bray Adams. An only child, he was named after his uncle Ansel Easton. his mother's family came from Baltimore. The Adams family came from new England. his parental grandfather founded and built a prosperous lumbar business, which his father later ran, through his father's natural talents lay more with sciences than with business. later is life, Adams would condemn that very dame industry for cutting down many of the great redwood forests.

In 1903, his family moved 2 miles west to a new home near the seacliff neighbourhood, just south of the presido army base. the home had a splendid view of the golden gate and the marine headlands. San Francisco was devastated by the april 18, 1906 earth quake. uninjured in the initial shaking, the four year old Ansel Easton Adams was tossed face first `into a garden wall during an aftershock three hours later, breaking and scarring his nose. Among his earliest memories was watching the smoke from the ensuring fire that destroyed much of the city a few miles to the east. although a doctor recommended that his nose be reset once he reached maturity, Ansel Easton Adams's nose remained crooked his entire life.

Ansel Easton Adams was a hyperactive child and prone to frequent sickness and hypochondria. he had a few friends, but his family home and surroundings on the heights facing the golden gate provided ample childhood activities. although he had no patience for games or sports, the curious child took to the beauty of the nature at an early age, collecting bugs and exploring lobos creek and all the way to baker beach and the sea cliffs leading to lands end.

His father bought a three inch telescope and they enthusiastically shared the hobby of amateur astronomy, visiting the lick observatory on mount hamilton together. his father went on to serve as the paid secretary-treasurer of the astronomical society of the pacific from 1925 to 1950.

After the death of Ansel's grandfather and the aftermath of the panic of 1907, his father;s business suffered great financial losses, some of the induced near-poverty was because Ansel's uncle Ansel Easton and Cedric Wright's father, George Wright, had secretly sold their shares of the company to the hawaiian sugar trust for a large amount of money. by 1912, the family's standard of living dropped sharply. after young Ansel was dismissed from several private school for his restlessness adn inattentiveness, his father decided to pull him out of school in 1915, at the age of 12. Adams was then educated by private tutors, his aunt Mary, and by his father. his aunt was a follower of Robert G Ingersoll, a 19th century agnostic, abolitionist and women's suffrage advocate. as a result of his aunt's influence, Robert's teachings were important to Ansel's upbringing.

His father raised him to follow the ideas of Ralph Waldo Emerson. "to live a modest, mortal life guided by a social responsibility to man and to nature." Adams had a warm adn supportive relationship with his father, but had a distant relationship with his mother, who did not approve of his interest in photography. the day after his mother's death on 1950, Ansel had a dispute with the undertaker when choosing which casket his mother would be buried in, Ansel chose the cheapest in the room, a $260 casket that seemed the least he could purchase without doing the job himself. when the undertaker remarked, "have you no respect for the dead?" Adams replied, "one more crack like that and i will take mama elsewhere."

Adams became interested in piano at the age 12. Music became the main focus of his youth. his father sent him to a piano teacher MArie Butler, who focused on perfectionism and accuracy. after four years of studying under her guidance, adams moved on to other teachers, one being composer Henry Cowell. for the next twelve years, the piano was Adam's primary occupation and by 1920, his intended profession. although he ultimately gave up music for photography, the piano bought substance, discipline and structure to his frustrating and erratic youth. moreover the careful training and exact craft required of a musician profoundly informed his visual artistry, as well as his influential writings and teachings on photography.

Adams first visited Yosemite National Park in 1916 with his family. He wrote of his first view of the valley: "the splendor of Yosemite burst upon us and it was glorious... One wonder after another descended upon us... There was light everywhere... A new era began for me." His father gave him his first camera, a Kodak Brownie box camera, during that stay and he took his first photographs with his "usual hyperactive enthusiasm".He returned to Yosemite on his own the following year with better cameras and a tripod. In the winter, he learned basic darkroomtechnique working part-time for a San Francisco photo finisher.Adams avidly read photography magazines, attended camera club meetings, and went to photography and art exhibits. With retired geologist and amateur ornithologist Francis Holman, whom he called "Uncle Frank," he explored the High Sierra, in summer and winter, developing the stamina and skill needed to photograph at high elevation and under difficult weather conditions

In 1927, Adams produced his first portfolio, Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras, in his new style, which included his famous image Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, taken with his Korona view camera using glass plates and a dark red filter (to heighten the tonal contrasts). On that excursion, he had only one plate left and he "visualized" the effect of the blackened sky before risking the last shot. He later said "I had been able to realize a desired image: not the way the subject appeared in reality but how it felt to me and how it must appear in the finished print". In April 1927, he wrote "My photographs have now reached a stage when they are worthy of the world's critical examination. I have suddenly come upon a new style which I believe will place my work equal to anything of its kind."

With the sponsorship and promotion of Albert Bender, an arts-connected businessman, Adams's first portfolio was a success (earning nearly $3,900) and soon he received commercial assignments to photograph the wealthy patrons who bought his portfolio. Adams also came to understand how important it was that his carefully crafted photos were reproduced to best effect. At Bender's invitation, he joined the Roxburghe Club, an association devoted to fine printing and high standards in book arts. He learned much about printing techniques, inks, design, and layout which he later applied to other projects.Unfortunately, at that time most of his darkroom work was still being done in the basement of his parents' home, and he was limited by barely adequate equipment.

Romantic landscape artists Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moranportrayed the Grand Canyon and Yosemite at the end of their reign, and were subsequently displaced by daredevil photographers Carleton Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge, and George Fiske.But it was Adams's black-and-white photographs of the West which became the foremost record of what many of the National Parks were like before tourism, and his persistent advocacy helped expand the National Park system. He used his works to promote many of the goals of the Sierra Club and of the nascent environmental movement, but always insisted that, as far as his photographs were concerned, "beauty comes first". His images are still very popular in calendars, posters, and books.

Realistic about development and the subsequent loss of habitat, Adams advocated for balanced growth, but was pained by the ravages of "progress". He stated, "We all know the tragedy of the dustbowls, the cruel unforgivable erosions of the soil, the depletion of fish or game, and the shrinking of the noble forests. And we know that such catastrophes shrivel the spirit of the people... The wilderness is pushed back, man is everywhere. Solitude, so vital to the individual man, is almost nowhere."

Adams co-founded Group f/64 with other masters like Edward Weston,Willard Van Dyke, and Imogen Cunningham. With Fred Archer, he pioneered the Zone System, a technique for translating perceived light into specific densities on negatives and paper, giving photographers better control over finished photographs. Adams also advocated the idea of visualization (which he often called "previsualization", though he later acknowledged that term to be a redundancy) whereby the final image is "seen" in the mind's eye before the photo is taken, toward the goal of achieving all together the aesthetic, intellectual, spiritual, and mechanical effects desired. He taught these and other techniques to thousands of amateur photographers through his publications and his workshops. His many books about photography, including the Morgan & Morgan Basic Photo Series (The Camera, The Negative, The Print, Natural Light Photography, and Artificial Light Photography) have become classics in the field.

In 1966 he was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1980 Jimmy Carter awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor.

Adams's photograph The Tetons and the Snake River was one of the 115 images recorded on the Voyager Golden Record aboard the Voyager spacecraft. These images were selected to convey information about humans, plants and animals, and geological features of the Earth to a possible alien civilization.

His legacy includes helping to elevate photography to an art comparable with painting and music, and equally capable of expressing emotion and beauty. He told his students, "It is easy to take a photograph, but it is harder to make a masterpiece in photography than in any other art medium."

Adams died on April 22, 1984, in the ICU at the Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula in Monterey, California, at the age of 82 fromcardiovascular disease. He was survived by his wife, two children, Michael and Anne, and five grandchildren.

Publishing rights for most of Adams's photographs are now handled by the trustees of The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. An archive of Ansel Adams's work is located at the Center for Creative Photography(CCP) at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Numerous works by the artist have been sold at auction, including a mural size print of 'CLEARING WINTER STORM, YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK' which sold at Sotheby's New York in 2010 for $722,500, the highest price ever paid for an original Ansel Adams photograph.

John Szarkowski states in the introduction to Ansel Adams: Classic Images (1985, p. 5), "The love that Americans poured out for the work and person of Ansel Adams during his old age, and that they have continued to express with undiminished enthusiasm since his death, is an extraordinary phenomenon, perhaps even unparalleled in our country's response to a visual artist."

Source: Wikipedia

Monday, February 22, 2016

In

famous photographers,

great quotes,

inspiration,

photography,

the world of photography,

what does it stand for

by Unknown

//

9:55 AM

//

Leave a Comment

What is photography really about

Photography is the science, art and practice of creating durable images by recording light or other electromagnetic radiation, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film.

“Photography is a way of feeling, of touching, of loving. What you have caught on film is captured forever… it remembers little things, long after you have forgotten everything.”

“Photography is an art of observation. It’s about finding something interesting in an ordinary place… I’ve found it has little to do with the things you see and everything to do with the way you see them.”

Typically, a lens is used to focus the light reflected or emitted from objects into a real image on the light-sensitive surface inside a cameraduring a timed exposure. With an electronic image sensor, this produces an electrical charge at each pixel, which is electronically processed and stored in a digital image file for subsequent display or processing. The result with photographic emulsion is an invisiblelatent image, which is later chemically "developed" into a visible image, either negative or positive depending on the purpose of the photographic material and the method of processing. A negative image on film is traditionally used to photographically create a positive image on a paper base, known as a print, either by using an enlarger or by contact printing.

Photography is employed in many fields of science, manufacturing (e.g., photolithography) and business, as well as its more direct uses for art, film and video production, recreational purposes, hobby, and mass communication.

“Photography to me is catching a moment which is passing, and which is true.”

“A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know.”

“Photography is a kind of virtual reality, and it helps if you can create the illusion of being in an interesting world.”

“Photography takes an instant out of time, altering life by holding it still.”

The word "photography" was created from the Greek roots φωτός (phōtos), genitive of φῶς (phōs), "light" and γραφή (graphé) "representation by means of lines" or "drawing", together meaning "drawing with light".

Several people may have coined the same new term from these roots independently. Hercules Florence, a French painter and inventor living in Campinas, Brazil, used the French form of the word, photographie, in private notes which a Brazilian photography historian believes were written in 1834. Johann von Maedler, a Berlin astronomer, is credited in a 1932 German history of photography as having used it in an article published on 25 February 1839 in the German newspaper Vossische Zeitung.Both of these claims are now widely reported but apparently neither has ever been independently confirmed as beyond reasonable doubt. Credit has traditionally been given to Sir John Herschel both for coining the word and for introducing it to the public. His uses of it in private correspondence prior to 25 February 1839 and at his Royal Society lecture on the subject in London on 14 March 1839 have long been amply documented and accepted as settled facts.

“Photography is a way to shape human perception.”

“Photography is the simplest thing in the world, but it is incredibly complicated to make it really work.”

“Photography is like a moment, an instant. You need a half-second to get the photo. So it’s good to capture people when they are themselves.”

“Photography is an immediate reaction, drawing is a meditation.”

“Photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event.”

“Photography is more than a medium for factual communication of ideas. It is a creative art.”

Around the year 1800, Thomas Wedgwood made the first known attempt to capture the image in a camera obscura by means of a light-sensitive substance. He used paper or white leather treated with silver nitrate. Although he succeeded in capturing the shadows of objects placed on the surface in direct sunlight, and even made shadow-copies of paintings on glass, it was reported in 1802 that "the images formed by means of a camera obscura have been found too faint to produce, in any moderate time, an effect upon the nitrate of silver." The shadow images eventually darkened all over.

The first permanent photoetching was an image produced in 1822 by the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce, but it was destroyed in a later attempt to make prints from it. Niépce was successful again in 1825. In 1826 or 1827, he made the View from the Window at Le Gras, the earliest surviving photograph from nature (i.e., of the image of a real-world scene, as formed in a camera obscura by alens).

“Photography is about finding out what can happen in the frame. When you put four edges around some facts, you change those facts.”

“Photography is truth. The cinema is truth twenty-four times per second.”

“Photography is pretty simple stuff. You just react to what you see, and take many, many pictures.”

“Photography is a small voice, at best, but sometimes one photograph, or a group of them, can lure our sense of awareness.”

“Photography is a reality so subtle that it becomes more real than reality.”

Because Niépce's camera photographs required an extremely long exposure (at least eight hours and probably several days), he sought to greatly improve his bitumen process or replace it with one that was more practical. In partnership with Louis Daguerre, he worked out post-exposure processing methods that produced visually superior results and replaced the bitumen with a more light-sensitive resin, but hours of exposure in the camera were still required. With an eye to eventual commercial exploitation, the partners opted for total secrecy.

Niépce died in 1833 and Daguerre then redirected the experiments toward the light-sensitive silver halides, which Niépce had abandoned many years earlier because of his inability to make the images he captured with them light-fast and permanent. Daguerre's efforts culminated in what would later be named the daguerreotype process, the essential elements of which were in place in 1837. The required exposure time was measured in minutes instead of hours. Daguerre took the earliest confirmed photograph of a person in 1838 while capturing a view of a Paris street: unlike the other pedestrian and horse-drawn traffic on the busy boulevard, which appears deserted, one man having his boots polished stood sufficiently still throughout the approximately ten-minute-long exposure to be visible. The existence of Daguerre's process was publicly announced, without details, on 7 January 1839. The news created an international sensation. France soon agreed to pay Daguerre a pension in exchange for the right to present his invention to the world as the gift of France, which occurred when complete working instructions were unveiled on 19 August 1839.

“Photography is a way of putting distance between myself and the work which sometimes helps me to see more clearly what it is that I have made.”

“Photography is a major force in explaining man to man.”

Meanwhile, in Brazil, Hercules Florence had apparently started working out a silver-salt-based paper process in 1832, later naming itPhotographie, and an English inventor, William Fox Talbot, succeeded in making crude but reasonably light-fast silver images on paper as early as 1834 but had kept his work secret. After reading about Daguerre's invention in January 1839, Talbot published his method and set about improving on it. At first, like other pre-daguerreotype processes, Talbot's paper-based photography typically required hours-long exposures in the camera, but in 1840 he created the calotype process, with exposures comparable to the daguerreotype. In both its original and calotype forms, Talbot's process, unlike Daguerre's, created a translucent negative which could be used to print multiple positive copies, the basis of most chemical photography up to the present day. Daguerreotypes could only be replicated by rephotographing them with a camera. Talbot's famous tiny paper negative of the Oriel window in Lacock Abbey, one of a number of camera photographs he made in the summer of 1835, may be the oldest camera negative in existence.

John Herschel made many contributions to the new field. He invented the cyanotype process, later familiar as the "blueprint". He was the first to use the terms "photography", "negative" and "positive". He had discovered in 1819 that sodium thiosulphate was a solvent of silver halides, and in 1839 he informed Talbot (and, indirectly, Daguerre) that it could be used to "fix" silver-halide-based photographs and make them completely light-fast. He made the first glass negative in late 1839.

In the March 1851 issue of The Chemist, Frederick Scott Archer published his wet plate collodion process. It became the most widely used photographic medium until the gelatin dry plate, introduced in the 1870s, eventually replaced it. There are three subsets to the collodion process; the Ambrotype (a positive image on glass), the Ferrotype or Tintype (a positive image on metal) and the glass negative, which was used to make positive prints on albumen or salted paper.

Many advances in photographic glass plates and printing were made during the rest of the 19th century. In 1891, Gabriel Lippmann introduced a process for making natural-color photographs based on the optical phenomenon of the interference of light waves. His scientifically elegant and important but ultimately impractical invention earned him the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1908.

Glass plates were the medium for most original camera photography from the late 1850s until the general introduction of flexible plastic films during the 1890s. Although the convenience of film greatly popularized amateur photography, early films were somewhat more expensive and of markedly lower optical quality than their glass plate equivalents, and until the late 1910s they were not available in the large formats preferred by most professional photographers, so the new medium did not immediately or completely replace the old. Because of the superior dimensional stability of glass, the use of plates for some scientific applications, such as astrophotography, continued into the 1990s, and in the niche field of laser holography it has persisted into the 2010s.

“Photography is the easiest medium with which to be merely competent. Almost anybody can be competent. It’s the hardest medium in which to have some sort of personal vision and to have a signature style.”

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

In

beginning,

birth of camera,

digital cameras,

evolution of camera,

SLR,

TLR

by Unknown

//

11:29 AM

//

1 comment

Evolution of Cameras

The history of the camera can be traced much further back than the introduction of photography. Cameras evolved from thecamera obscura, and continued to change through many generations of photographic technology, including daguerreotypes,calotypes, dry plates, film, and digital cameras.

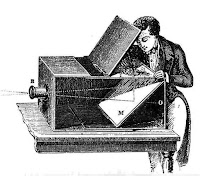

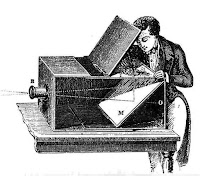

Camera obscura

Photographic cameras were a development of the camera obscura, a device possibly dating back to the ancient Chinese and ancient Greeks which uses a pinhole or lens to project an image of the scene outside upside-down onto a viewing surface.

An Arab physicist, Ibn al-Haytham, published his Book of Optics in 1021 AD. He created the first pinhole camera after observing how light traveled through a window shutter. Ibn al-Haytham realized that smaller holes would create sharper images. Ibn al-Haytham is also credited with inventing the first camera obscura.

An Arab physicist, Ibn al-Haytham, published his Book of Optics in 1021 AD. He created the first pinhole camera after observing how light traveled through a window shutter. Ibn al-Haytham realized that smaller holes would create sharper images. Ibn al-Haytham is also credited with inventing the first camera obscura.

After Niépce's death in 1833, his partner Louis Daguerre continued to experiment and by 1837 had created the first practical photographic process, which he named the daguerreotype and publicly unveiled in 1839. Daguerre treated a silver-plated sheet of copper with iodine vapor to give it a coating of light-sensitive silver iodide. After exposure in the camera, the image was developed by mercury vapor and fixed with a strong solution of ordinary salt (sodium chloride). Henry Fox Talbot perfected a different process, the calotype, in 1840. As commercialized, both processes used very simple cameras consisting of two nested boxes. The rear box had a removable ground glass screen and could slide in and out to adjust the focus. After focusing, the ground glass was replaced with a light-tight holder containing the sensitized plate or paper and the lens was capped. Then the photographer opened the front cover of the holder, uncapped the lens, and counted off as many seconds—or minutes—as the lighting conditions seemed to require before replacing the cap and closing the holder. Despite this mechanical simplicity, high-quality achromatic lenses were standard.

The use of photographic film was pioneered by George Eastman, who started manufacturing paper film in 1885 before switching to celluloid in 1889. His first camera, which he called the "Kodak," was first offered for sale in 1888. It was a very simple box camera with a fixed-focus lens and single shutter speed, which along with its relatively low price appealed to the average consumer. The Kodak came pre-loaded with enough film for 100 exposures and needed to be sent back to the factory for processing and reloading when the roll was finished. By the end of the 19th century Eastman had expanded his lineup to several models including both box and folding cameras.

The use of photographic film was pioneered by George Eastman, who started manufacturing paper film in 1885 before switching to celluloid in 1889. His first camera, which he called the "Kodak," was first offered for sale in 1888. It was a very simple box camera with a fixed-focus lens and single shutter speed, which along with its relatively low price appealed to the average consumer. The Kodak came pre-loaded with enough film for 100 exposures and needed to be sent back to the factory for processing and reloading when the roll was finished. By the end of the 19th century Eastman had expanded his lineup to several models including both box and folding cameras.

The first practical reflex camera was the Franke & Heidecke Rolleiflex medium format TLR of 1928. Though both single- and twin-lens reflex cameras had been available for decades, they were too bulky to achieve much popularity. The Rolleiflex, however, was sufficiently compact to achieve widespread popularity and the medium-format TLR design became popular for both high- and low-end cameras.

The first practical reflex camera was the Franke & Heidecke Rolleiflex medium format TLR of 1928. Though both single- and twin-lens reflex cameras had been available for decades, they were too bulky to achieve much popularity. The Rolleiflex, however, was sufficiently compact to achieve widespread popularity and the medium-format TLR design became popular for both high- and low-end cameras.

The move to digital formats was helped by the formation of the first JPEG and MPEG standards in 1988, which allowed image and video files to be compressed for storage. The first consumer camera with a liquid crystal display on the back was the Casio QV-10 developed by a team led by Hiroyuki Suetaka in 1995. The first camera to use CompactFlash was the Kodak DC-25 in 1996. The first camera that offered the ability to record video clips may have been the Ricoh RDC-1 in 1995.

The move to digital formats was helped by the formation of the first JPEG and MPEG standards in 1988, which allowed image and video files to be compressed for storage. The first consumer camera with a liquid crystal display on the back was the Casio QV-10 developed by a team led by Hiroyuki Suetaka in 1995. The first camera to use CompactFlash was the Kodak DC-25 in 1996. The first camera that offered the ability to record video clips may have been the Ricoh RDC-1 in 1995.

Camera obscura

Photographic cameras were a development of the camera obscura, a device possibly dating back to the ancient Chinese and ancient Greeks which uses a pinhole or lens to project an image of the scene outside upside-down onto a viewing surface.

An Arab physicist, Ibn al-Haytham, published his Book of Optics in 1021 AD. He created the first pinhole camera after observing how light traveled through a window shutter. Ibn al-Haytham realized that smaller holes would create sharper images. Ibn al-Haytham is also credited with inventing the first camera obscura.

An Arab physicist, Ibn al-Haytham, published his Book of Optics in 1021 AD. He created the first pinhole camera after observing how light traveled through a window shutter. Ibn al-Haytham realized that smaller holes would create sharper images. Ibn al-Haytham is also credited with inventing the first camera obscura.

On 24 January 1544 mathematician and instrument maker Reiners Gemma Frisius of Leuven University used one to watch a solar eclipse, publishing a diagram of his method in De Radio Astronimica et Geometrico in the following year. In 1558 Giovanni Batista della Porta was the first to recommend the method as an aid to drawing.

Before the invention of photographic processes there was no way to preserve the images produced by these cameras apart from manually tracing them. The earliest cameras were room-sized, with space for one or more people inside; these gradually evolved into more and more compact models such as that by Niépce's time portable handheld cameras suitable for photography were readily available. The first camera that was small and portable enough to be practical for photography was envisioned by Johann Zahn in 1685, though it would be almost 150 years before such an application was possible.

Early fixed images

The first partially successful photograph of a camera image was made in approximately 1816 by Nicéphore Niépce, using a very small camera of his own making and a piece of paper coated with silver chloride, which darkened where it was exposed to light. No means of removing the remaining unaffected silver chloride was known to Niépce, so the photograph was not permanent, eventually becoming entirely darkened by the overall exposure to light necessary for viewing it. In the mid-1820s, Niépce used a sliding wooden box camera made by Parisian opticians Charles and Vincent Chevalier to experiment with photography on surfaces thinly coated with Bitumen of Judea. The bitumen slowly hardened in the brightest areas of the image. The unhardened bitumen was then dissolved away. One of those photographs has survived.

Daguerrotypes and Calotypes

Kodak and the birth of film

The use of photographic film was pioneered by George Eastman, who started manufacturing paper film in 1885 before switching to celluloid in 1889. His first camera, which he called the "Kodak," was first offered for sale in 1888. It was a very simple box camera with a fixed-focus lens and single shutter speed, which along with its relatively low price appealed to the average consumer. The Kodak came pre-loaded with enough film for 100 exposures and needed to be sent back to the factory for processing and reloading when the roll was finished. By the end of the 19th century Eastman had expanded his lineup to several models including both box and folding cameras.

The use of photographic film was pioneered by George Eastman, who started manufacturing paper film in 1885 before switching to celluloid in 1889. His first camera, which he called the "Kodak," was first offered for sale in 1888. It was a very simple box camera with a fixed-focus lens and single shutter speed, which along with its relatively low price appealed to the average consumer. The Kodak came pre-loaded with enough film for 100 exposures and needed to be sent back to the factory for processing and reloading when the roll was finished. By the end of the 19th century Eastman had expanded his lineup to several models including both box and folding cameras.

In 1900, Eastman took mass-market photography one step further with the Brownie, a simple and very inexpensive box camera that introduced the concept of the snapshot. The Brownie was extremely popular and various models remained on sale until the 1960s.

Film also allowed the movie camera to develop from an expensive toy to a practical commercial tool.

Despite the advances in low-cost photography made possible by Eastman, plate cameras still offered higher-quality prints and remained popular well into the 20th century. To compete with roll film cameras, which offered a larger number of exposures per loading, many inexpensive plate cameras from this era were equipped with magazines to hold several plates at once. Special backs for plate cameras allowing them to use film packs or roll film were also available, as were backs that enabled rollfilm cameras to use plates.

Except for a few special types such as Schmidt cameras, most professional astrographs continued to use plates until the end of the 20th century when electronic photography replaced them.

TLRs and SLRs

The first practical reflex camera was the Franke & Heidecke Rolleiflex medium format TLR of 1928. Though both single- and twin-lens reflex cameras had been available for decades, they were too bulky to achieve much popularity. The Rolleiflex, however, was sufficiently compact to achieve widespread popularity and the medium-format TLR design became popular for both high- and low-end cameras.

The first practical reflex camera was the Franke & Heidecke Rolleiflex medium format TLR of 1928. Though both single- and twin-lens reflex cameras had been available for decades, they were too bulky to achieve much popularity. The Rolleiflex, however, was sufficiently compact to achieve widespread popularity and the medium-format TLR design became popular for both high- and low-end cameras.

A similar revolution in SLR design began in 1933 with the introduction of the Ihagee Exakta, a compact SLR which used 127 rollfilm. This was followed three years later by the first Western SLR to use 135 film, the Kine Exakta (World's first true 35mm SLR was Soviet "Sport" camera, marketed several months before Kine Exakta, though "Sport" used its own film cartridge). The 35mm SLR design gained immediate popularity and there was an explosion of new models and innovative features after World War II. There were also a few 35mm TLRs, the best-known of which was the Contaflex of 1935, but for the most part these met with little success.

The first major post-war SLR innovation was the eye-level viewfinder, which first appeared on the Hungarian Duflex in 1947 and was refined in 1948 with the Contax S, the first camera to use a pentaprism. Prior to this, all SLRs were equipped with waist-level focusing screens. The Duflex was also the first SLR with an instant-return mirror, which prevented the viewfinder from being blacked out after each exposure. This same time period also saw the introduction of the Hasselblad 1600F, which set the standard for medium format SLRs for decades.

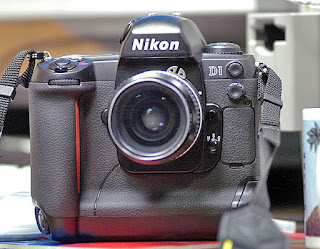

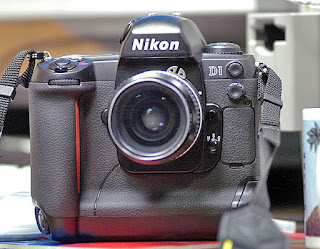

In 1952 the Asahi Optical Company (which later became well known for its Pentax cameras) introduced the first Japanese SLR using 135 film, the Asahiflex. Several other Japanese camera makers also entered the SLR market in the 1950s, including Canon, Yashica, and Nikon. Nikon's entry, the Nikon F, had a full line of interchangeable components and accessories and is generally regarded as the first Japanese system camera. It was the F, along with the earlier S series of rangefinder cameras, that helped establish Nikon's reputation as a maker of professional-quality equipment.

Arrival of true digital cameras

By the late 1980s, the technology required to produce truly commercial digital cameras existed. The first true portable digital camera that recorded images as a computerized file was likely the Fuji DS-1P of 1988, which recorded to a 2 MB SRAM memory card that used a battery to keep the data in memory. This camera was never marketed to the public.

The first digital camera of any kind ever sold commercially was possibly the MegaVision Tessera in 1987 though there is not extensive documentation of its sale known. The first portable digital camera that was actually marketed commercially was sold in December 1989 in Japan, the DS-X by Fuji The first commercially available portable digital camera in the United States was the Dycam Model 1, first shipped in November 1990. It was originally a commercial failure because it was black and white, low in resolution, and cost nearly $1,000 (about $2000 in 2014). It later saw modest success when it was re-sold as the Logitech Fotoman in 1992. It used a CCD image sensor, stored pictures digitally, and connected directly to a computer for download.

In 1991, Kodak brought to market the Kodak DCS (Kodak Digital Camera System), the beginning of a long line of professional Kodak DCSSLR cameras that were based in part on film bodies, often Nikons. It used a 1.3 megapixel sensor, had a bulky external digital storage system and was priced at $13,000. At the arrival of the Kodak DCS-200, the Kodak DCS was dubbed Kodak DCS-100.

The move to digital formats was helped by the formation of the first JPEG and MPEG standards in 1988, which allowed image and video files to be compressed for storage. The first consumer camera with a liquid crystal display on the back was the Casio QV-10 developed by a team led by Hiroyuki Suetaka in 1995. The first camera to use CompactFlash was the Kodak DC-25 in 1996. The first camera that offered the ability to record video clips may have been the Ricoh RDC-1 in 1995.

The move to digital formats was helped by the formation of the first JPEG and MPEG standards in 1988, which allowed image and video files to be compressed for storage. The first consumer camera with a liquid crystal display on the back was the Casio QV-10 developed by a team led by Hiroyuki Suetaka in 1995. The first camera to use CompactFlash was the Kodak DC-25 in 1996. The first camera that offered the ability to record video clips may have been the Ricoh RDC-1 in 1995.

In 1995 Minolta introduced the RD-175, which was based on the Minolta 500si SLR with a splitter and three independent CCDs. This combination delivered 1.75M pixels. The benefit of using an SLR base was the ability to use any existing Minolta AF mount lens. 1999 saw the introduction of the Nikon D1, a 2.74 megapixel camera that was the first digital SLR developed entirely from the ground up by a major manufacturer, and at a cost of under $6,000 at introduction was affordable by professional photographers and high-end consumers. This camera also used Nikon F-mount lenses, which meant film photographers could use many of the same lenses they already owned.

Digital camera sales continued to flourish, driven by technology advances. The digital market segmented into different categories, Compact Digital Still Cameras, Bridge Cameras, Mirrorless Compacts and Digital SLRs. One of the major technology advances was the development of CMOS sensors, which helped drive sensor costs low enough to enable the widespread adoption of camera phones.

Source: Wikipedia

Popular Posts

-

Abstract Photography Abstract photography is my personal favourite kind of photography. I have always been fascinated by the creativity...

-

Food Photography Food photography is a still life photography genre used to create attractive still life photographs of food. It ...

-

Its amazing how things work out.. I've been wanting to write this post from January of last year. Finally found the time and motivation...

-

Landscape Photography Landscape photography shows spaces within the world, sometimes vast and unending, but other times microscopic....

-

Aerial Photography Aerial photography is the taking of photographs of the ground from an elevated/direct-down position. Usua...